Distributions

Distributions¶

Our space is the outcomes of five rolls of a die, and our random variable $S$ is the total number of spots on the five rolls.

five_rolls_sum

In the last section we found $P(S = 10)$. We could use that same process to find $P(S = s)$ for each possible value of $s$. The group method allows us to do this for all $s$ at the same time.

To do this, we will start by dropping the omega column. Then we will group the table by the distinct values of S(omega), and use sum to add up all the probabilities in each group.

dist_S = five_rolls_sum.drop('omega').group('S(omega)', sum)

dist_S

This table shows all the possible values of $S$ along with all their probabilities. It is called a probability distribution table for $S$.

The contents of the table – all the possible values of the random variable, along with all their probabilities – are called the probability distribution of $S$, or just distribution of $S$ for short. The distribution shows how the total probability of 100% is distributed over all the possible values of $S$.

Let's check this, to make sure that all the $\omega$'s in the outcome space have been accounted for in the column of probabilities.

dist_S.column(1).sum()

That's 1 in a computing environment. This is a feature of any probability distribution:

Probabilities in a distribution are non-negative and sum to 1.

Visualizing the Distribution¶

In Data 8 you used the datascience library to work with distributions of data. The prob140 library builds on datascience to provide some convenient tools for working with probability distributions and events.

First, we will construct a probability distribution object which, while it looks very much like the table above, expects a probability distribution in the second column and complains if it finds anything else.

To keep the code easily readable, let's extract the possible values and probabilities separately as arrays:

s = dist_S.column(0)

p_s = dist_S.column(1)

To turn these into a probability distribution object, start with an empty table and use the values and probability Table methods. The argument of values is a list or an array of possible values, and the argument of probability is a list or an array of the corresponding probabilities.

dist_S = Table().values(s).probability(p_s)

dist_S

That looks exactly like the table we had before except for more readable column labels. But now for the benefit: to visualize the distribution in a histogram, just use the prob140 method Plot as follows.

Plot(dist_S)

Notes on Plot¶

Recall that

histin thedatasciencelibrary displays a histogram of raw data contained in a column of a table.Plotin theprob140library displays a probability histogram based on a probability distribution as the input.Plotonly works on probability distribution objects created using thevaluesandprobabilitymethods. It won't work on a general member of theTableclass.Plotworks well with random variables that have integer values. Many of the random variables you will encounter in the next few chapters will be integer-valued. For displaying the distributions of other random variables, binning decisions are more complicated.

Notes on the Distribution of $S$¶

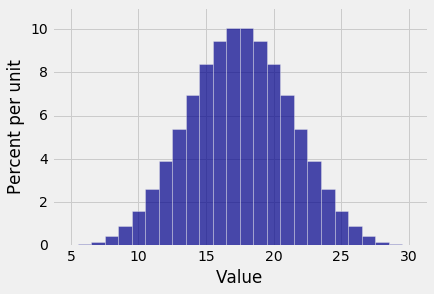

Here we have the bell shaped curve appearing as the distribution of the sum of five rolls of a die. Notice two differences between this histogram and the bell shaped distributions you saw in Data 8.

- This one displays an exact distribution. It was computed based on all the possible outcomes of the experiment. It is not an approximation nor an empirical histogram.

- The statement of the Central Limit Theorem in Data 8 said that the distribution of the sum of a large random sample is roughly normal. But here you're seeing a bell shaped distribution for the sum of only five rolls. If you start out with a uniform distribution (which is the distribution of a single roll), then you don't need a large sample before the probability distribution of the sum starts to look normal.

Visualizing Probabilities of Events¶

As you know from Data 8, the interval between the points of inflection of the bell curve contains about 68% of the area of the curve. Though the histogram above isn't exactly a bell curve – it is a discrete histogram with only 26 bars – it's pretty close. The points of inflection appear to be 14 and 21, roughly.

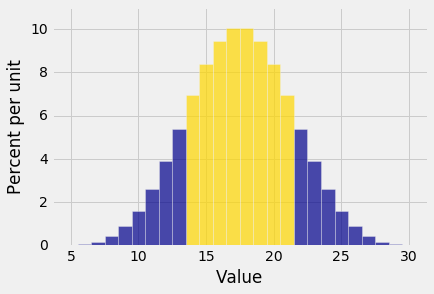

The event argument of Plot lets you visualize the probability of the event, as follows.

Plot(dist_S, event = np.arange(14, 22, 1))

The gold area is the equal to $P(14 \le S \le 21)$.

The prob_event method operates on probability distribution objects to return the probability of an event. To find $P(14 \le S \le 21)$, use it as follows.

dist_S.prob_event(np.arange(14, 22, 1))

The chance is 69.6%, not very far from 68%.

Math and Code Correspondence¶

$P(14 \le S \le 21)$ can be found by partitioning the event as the union of the events $\{S = s\}$ in the range 14 through 21, and using the addition rule. $$ P(14 \le S \le 21) = \sum_{s = 14}^{21} P(S = s) $$

Note carefully the use of lower case $s$ for the generic possible value, in contrast with upper case $S$ for the random variable; not doing so leads to endless confusion about what formulas mean.

This one means:

- First extract the event $\{ S = s\}$ for each value $s$ in the range 14 through 21:

event_table = dist_S.where(0, are.between(14, 22))

event_table

- Then add the probabilities of all those events:

event_table.column('Probability').sum()

The prob_event method does all this in one step. Here it is again, for comparison.

dist_S.prob_event(np.arange(14, 22, 1))

You can use the same basic method in various ways to find the probability of any event determined by $S$. Here are two examples.

Example 1. $$ P(S^2 = 400) = P(S = 20) = 8.37\% $$ from the table above.

Example 2. $$ P(S > 20) = \sum_{s=20}^{30} P(S = s) $$

A quick way of finding the numerical value:

dist_S.prob_event(np.arange(20, 31, 1))

Example 3. $$ P(\big{\vert} S - 10 \big{|} \le 6) ~ = ~ P(4 \le S \le 16) ~ = ~ \sum_{s=4}^{16} P(S=s) $$

dist_S.prob_event(np.arange(4, 17, 1))