Exponential Distribution

Exponential Distribution¶

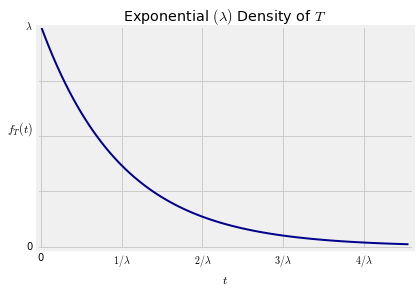

A random variable $T$ has the exponential distribution with parameter $\lambda$ if the density of $T$ is given by

$$ f_T(t) ~ = \lambda e^{-\lambda t}, ~~~ t \ge 0 $$As you found by using SymPy, the cdf of $T$ is

and $$ E(T) ~ = ~ \frac{1}{\lambda} ~ = ~ SD(T) $$

The graph below shows the density $f_T$ with the labeled points on the horizontal axis corresponding to standard units of -1, 0, 1, 2, and 3. The random variable $T$ can't be negative, and the density doesn't go further than 1 SD below the mean. The spread comes from the long right hand tail.

CDF and Survival Function¶

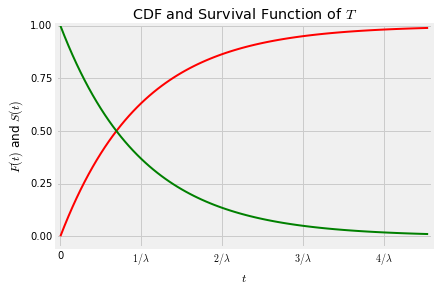

The exponential distribution is often used as a model for random lifetimes, in settings that we will study in greater detail below. For now, just think of $T$ as a lifetime of an object like a lightbulb, and note that the cdf at time $t$ can be thought of as the chance that the object dies before time $t$:

$$ P(T \le t) ~ = ~ F_T(t) ~ = ~ 1 - e^{-\lambda t} $$The complementary event is that the object survives past time $t$, and therefore its probability defines the survival function $S_T$:

$$ S_T(t) ~ = ~ P(T > t) ~ = ~ 1 - F_T(t) ~ = ~ e^{-\lambda t} $$Here is the graph of the cdf (red) and the survival function (green). The values of both the functions are probabilities, so the vertical axis is the probability scale.

Median¶

Notice that the two curves intersect at the vertical level 0.5. If $t_{0.5}$ is the value of $t$ at which the curves intersect, then

$$ S_T(t_{0.5}) = 1 - F_T(t_{0.5}) ~~~~ \text{and} ~~~~ S_T(t_{0.5}) = F_T(t_{0.5}) $$and therefore $$ P(T > t_{0.5}) = S_T(t_{0.5}) = 0.5 = F_T(t_{0.5}) = P(T \le t_{0.5}) $$

The point $t_{0.5}$ is called the median of the distribution. We can find $t_{0.5}$ in terms of $\lambda$ by using the formula for the survival function.

$$ e^{-\lambda t_{0.5}} = 0.5 ~ \iff ~ -\lambda t_{0.5} = \log(0.5) ~ \iff ~ \lambda t_{0.5} = \log(2) ~ \iff ~ t_{0.5} = \frac{\log(2)}{\lambda} = \log(2)E(T) $$Because $\log(2) < 1$, the median lifetime $t_{0.5}$ is less than the mean lifetime $E(T) = 1/\lambda$ as you can see on the graph. This is consistent with an observation you made in Data 8: if a distribution has a right hand tail, the mean is greater than the median.

The exponential distribution is often used to model lifetimes of objects like radioactive atoms which undergo exponential decay. The half life of a radioactive isotope is defined as the time by which half of the atoms of the isotope will have decayed. That is, the half life is the median of the exponential lifetime of the atom. The parameter $\lambda$ is called the decay rate of the atom. By the property of the median $t_{0.5}$ derived above, the relation between $\lambda$ and the half life is

$$ \text{half life} = \frac{\log(2)}{\lambda} $$Memoryless Property¶

Let $s$ and $t$ be positive, and let's find the conditional probability that the object survives a further $s$ units of time given that it has already survived $t$.

$$ P(T > t+s \mid T > t) = \frac{P(T > t+s, T > t)}{P(T > t)} = \frac{P(T > t+s)}{P(T > t)} = \frac{e^{-\lambda(t+s)}}{e^{-\lambda t}} = e^{-\lambda s} = P(T > s) $$Notice that $t$ does not appear in the answer. So for example the chance that the object survives an additional year given that it has been alive for 50 years is the same as the chance that is survives a year when it starts out brand new. It forgets that it has already lived 50 years.

This is called the memoryless property of the exponential distribution. It can be shown that the exponential and the geometric are the only two distributions that have the memoryless property.

The memoryless property is an excellent reason not to use the exponential distribution to model the lifetimes of people or of anything that ages. For lifetimes of things like lightbulbs or radioactive atoms, the exponential distribution often does fine.

As we will see later, the exponential distribution arises in many other settings. For now we will investigate whether there is one fundamental exponential distribution from which all the others can be derived, just as the uniform distribution on any interval can be dervied from the uniform distribution on $(0, 1)$.