Random Counts

Random Counts¶

These form a class of random variables that is of fundamental importance in probability theory. You have seen an example already: the number of matches (fixed points) in a random permutation of $n$ elements is an example of a "random count". You can think of each element as a trial, and a match as a "success". Then the "number of matches" is another way of expressing the random number of successes among the $n$ trials.

Bernoulli $(p)$ Distributions¶

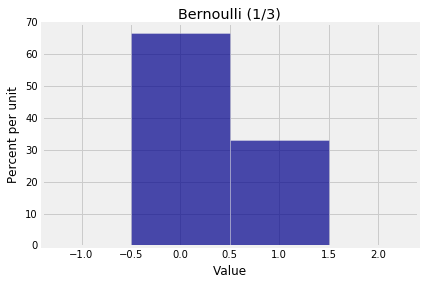

The smallest possible number of trials is 1, and results in either 0 successes or 1 success. The resulting distribution on those two values is called the Bernoulli $(p)$ distribution, where $p$ is the probability of success.

Here is the probability histogram of the Bernoulli $(1/3)$ distribution.

bern_13 = Table().values([0,1]).probability([2/3, 1/3])

Plot(bern_13)

plt.title('Bernoulli (1/3)');

Let $X_1, X_2, \ldots, X_n$ be random variables defined on a common probability space, and let each be a Bernoulli $(p)$ random variable. Then $X_i$ can be thought of as "the number of successes in Trial $i$".

The sum of these $n$ counts $$ S_n = X_1 + X_2 + \cdots + X_n $$ is then the total number of successes in the $n$ trials. For example, if $n=3$ and $X_1 = 0$, $X_2 = 0$, and $X_3 = 1$, then there is one success in the three trials and $S_3 = 1$.

If $p = 1/n$, you can place these random variables in the context of the matching problem. Suppose you have a random permuatation of $\{1, 2, \ldots n\}$. For each $i$, let $X_i$ count the number of matches at Position $i$. Then $X_i$ is a Bernoulli $(1/n)$ random variable, by results we proved in an earlier chapter. Also, $S_n$ as defined above is the number of matches in the permutation.

We figured out earlier that $$ P(S_n = 0) = 1 - \frac{1}{1!} + \frac{1}{2!} - \frac{1}{3!} + \cdots + (-1)^n\frac{1}{n!} $$

To find the distribution of $S_n$ we will need $P(S_n = k)$ for $k = 1, 2, \ldots, n$ as well. The calculation has to take into account the fact that the $X_i$'s are not independent of each other. For example, $$ P(X_n = 1 \mid X_1 = 1, X_2 = 1, \ldots, X_{n-1} = 1) = 1 \ne \frac{1}{n} = P(X_n = 1) $$

Given that the first $n-1$ letters fell in their matching envelopes, the $n$th one has to do so too – there is nowhere else for it to go.

Such dependences mean that we have to be very careful in our calculations of the distribution of the number of matches. We will outline the calculation in a later exercise.

In this chapter, we will start out with the much simpler case when all the $X_i$'s are i.i.d. That is, trials are independent of each other, and chance of success in a fixed trial is the same for all trials.

To fix such an example in your mind, think of the trials as being 7 rolls of a die, and let $S_7$ be the number of sixes in the 7 rolls. Then each $X_i$ as defined above has the Bernoulli $(1/6)$ distribution and all the $X_i$'s are independent.