Linear Transformations

Let T have the exponential (λ) distribution and let T1=λT. Then T1 is a linear transformation of T. Therefore

E(T1)=λE(T)=1 and SD(T1)=λSD(T)=1The parameter λ has disappeared in these results. Let’s see how that follows from the distribution of T1. The cdf of T1 is

FT1(t)=P(T1≤t)=P(T≤t/λ)=1−e−λ(t/λ)=1−e−tThat’s the cdf of the exponential (1) distribution, consistent with the expectation and SD we found above.

To summarize, if T has the exponential (λ) distribution then the distribution of T1=λT is exponential (1).

You can think of the exponential (1) distribution as the fundamental member of the family of exponential distributions. All others in the family can be found by changing the scale of measurement, that is, by multiplying by a constant.

Scale Parameter

Conversely if T1 has the exponential (1) distribution, then T=1λT1 has the exponential (λ) distribution. The factor 1/λ is called the scale parameter.

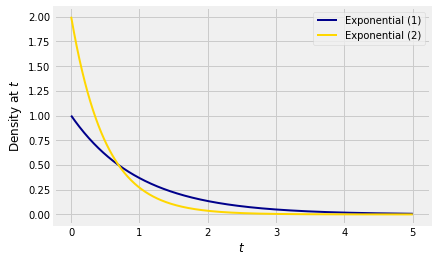

Here are graphs of the densities of T1 and T=12T1. We know that T has the exponential (2) distribution.

The formulas for the two densities are

fT1(s)=e−s fT(t)=2e−2tLet’s try to understand the relation between these two densities in a way that will help us generalize what we are seeing in this example.

The relation between the two random variables is T=12T1.

- For any t, the chance that T is near t is the same as the chance that T1 is near s=2t. This explains the factor e−2t in the density of T.

- If we think of T1 as a point on the horizontal axis, then to create T you have to divide T1 by 2. So the transformation consists of halving all distances on the horizontal axis. The total area under the density of T must equal 1, so we have to compensate by doubling all distances on the vertical axis. This explains the factor 2 in the density of T.

Linear Change of Variable Formula for Densities

We use the same idea to find the density of a linear transformation of a random variable.

Let X be a random variable with density fX, and let Y=aX+b for constants a≠0 and b. Let fY be the density of Y. Then

fY(y) = fX(y−ba)1|a|Let’s take this formula in two pieces, as in the exponential example.

- For Y to be y, X has to be (y−b)/a.

- The linear function y=ax+b involves multiplying distances along the horizontal axis by |a|; the sign of a doesn’t affect distances. To get a density, we have to compensate by dividing all vertical distances by |a|.

This is a good way to understand the formula, and will help you understand the corresponding formula for non-linear transformations.

For a formal proof, start with the case a>0.

FY(y)=P(aX+b≤y)=P(X≤y−ba)=FX(y−ba)By the chain rule of differentiation,

fY(y)=fX(y−ba)⋅1aIf a<0 then division by a causes the direction of the inequality to switch:

FY(y)=P(aX+b≤y)=P(X≥y−ba)=1−FX(y−ba)Now the chain rule yields

fY(y) = −fX(y−ba)⋅1a = fX(y−ba)⋅1|a|The Normal Densities

Let Z have the standard normal density

ϕ(z) = 1√2πe−12z2, −∞<z<∞Let X=σZ+μ for constants μ and σ with σ>0. Then for any real number x, the density of X is

fX(x) = ϕ(x−μσ)1σ= 1√2πσe−12(x−μσ)2Thus every normal random variable is a linear transformation of a standard normal variable.

The Uniform Densities, Revisited

Let the distribution of U be uniform on (0,1) and for constants b>a let V=(b−a)U+a. In an earlier section we saw that V has the uniform distribution on (a,b). But let’s see what’s involved in confirming that result using our new formula.

First it is a good idea to be clear about the possible values of V. Since the possible values of U are in (0,1), the possible values of V are in (a,b).

At v∈(a,b), the density of V is

fV(v) = fU(v−ab−a)1b−a = 1⋅1b−a = 1b−aThat’s the uniform density on (a,b).