Chernoff Bound

If the form of a distribution is intractable in that it is difficult to find exact probabilities by integration, then good estimates and bounds become important. Bounds on the tails of the distribution of a random variable help us quantify roughly how close to the mean the random variable is likely to be.

We already know two such bounds. Let X be a random variable with expectation μ and SD σ.

Markov’s Bound on the Right Hand Tail

If X is non-negative,

P(X≥c) ≤ μcChebychev’s Bound on Two Tails

P(|X−μ|≥c) ≤ σ2c2Moment generating functions can help us improve upon these bounds in many cases. In what follows, we will assume that the moment generating function of X is finite over the whole real line. If it is finite only over a smaller interval around 0, the calculations of the mgf below should be confined to that interval.

Chernoff Bound on the Right Tail

Observe that if g is an increasing function, then the event X≥c is the same as the event g(X)≥g(c).

For any fixed t>0, the function defined by g(x)=etx is increasing as well as non-negative. So for each t>0,

P(X≥c) =P(etX≥etc)≤ E(etX)etc (Markov's bound)= MX(t)etcThis is the first step in developing a Chernoff bound on the right hand tail.

For the next step, notice that you can choose t to be any positive number. Some choices of t will give sharper bounds than others. Because these are upper bounds, the sharpest among all of the bounds will correspond to the value of t that minimizes the right hand side. So the Chernoff bound has an optimized form:

P(X≥c) ≤ mint>0MX(t)etcApplication to the Normal Distribution

Suppose X has the normal (μ,σ2) distribution and we want to get a sense of how far X can be above the mean. Fix c>0. The exact chance that the value of X is at least c above the mean is

P(X−μ≥c) = 1−Φ(c/σ)because the distribution of X−μ is normal (0,σ2). This exact answer looks neat and tidy, but the standard normal cdf Φ is not easy to work with analytically. Sometimes we can gain more insight from a good bound.

The optimized Chernoff bound is

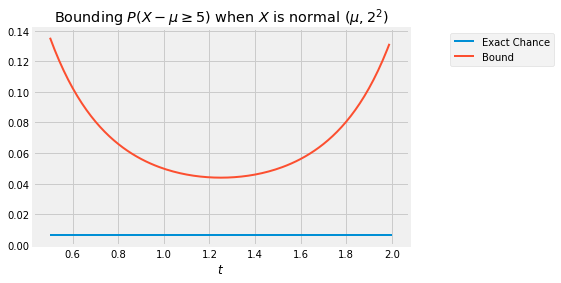

P(X−μ≥c) ≤ mint>0MX−μ(t)etc= mint>0eσ2t2/2etc= mint>0e−ct+σ2t2/2The curve below is the graph of exp(−ct+σ2t2/2) as a function of t, in the case σ=2 and c=5. The flat line is the exact probability of P(X−μ≥c). The curve is always above the flat line: no matter what t is, the bound is an upper bound. The sharpest of all the upper bounds corresponds to the minimizing value t∗ which is somewhere in the 1.2 to 1.3 range.

To find the minimizing value of t analytically, we will use the standard calculus method of minimization. But first we will simplify our calculations by observing that finding the point at which a positive function is minimized is the same as finding the point at which the log of the function is minimized. This is because log is an increasing function.

So the problem reduces to finding the value of t that minimizes the function h(t)=−ct+σ2t2/2. By differentiation, the minimizing value of t solves

c = σ2t∗and hence

t∗ = cσ2So the Chernoff bound is

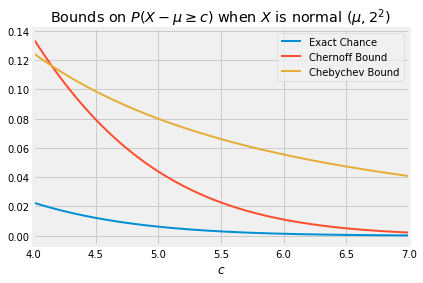

P(X−μ≥c) ≤ e−ct∗+σ2t∗2/2 = e−c2/2σ2Compare this with the bounds we already have. Markov’s bound can’t be applied directly as X−μ can have negative values. Because the distribution of X−μ is symmetric about 0, Chebychev’s bound becomes

P(X−μ≥c) ≤ σ22c2When c is large, the optimized Chernoff bound is quite a bit sharper than Chebychev’s. In the case σ=2, the graph below shows the exact value of P(X−μ≥c) as a function of c, along with the Chernoff and Chebychev bounds.

Chernoff Bound on the Left Tail

By an analogous argument we can derive a Chernoff bound on the left tail of a distribution. For a fixed t>0, the function g(x)=e−tx is decreasing and non-negative. So for t>0 and any fixed c,

P(X≤c) = P(e−tX≥e−tc) ≤ E(e−tX)e−tc = MX(−t)e−tcand therefore

P(X≤c) ≤ mint>0MX(−t)e−tcSums of Independent Random Variables

The Chernoff bound is often applied to sums of independent random variables. Let X1,X2,…,Xn be independent and let Sn=X1+X2+…+Xn. Fix any number c. For every t>0,

P(Sn≥c) ≤ MSn(t)etc = ∏ni=1MXi(t)etcThis result is useful for finding bounds on binomial tails because the moment generating function of a Bernoulli random variable has a straightforward form. It is also used for bounding tails of sums of independent indicators with possibly different success probabilities. We will leave all this for a subsequent course.