Maximum Likelihood

Suppose you have an i.i.d. sample X1,X2,…,Xn where the density of each Xi depends on a parameter θ.

Assume that θ is fixed but unknown. The method of maximum likelihood estimates θ by answering the following question:

Among all the possible values of the parameter θ, which one maximizes the likeihood of getting our sample?

That maximizing value of the parameter is called the maximum likelihood estimate or MLE for short. In this section we will develop a method for finding MLEs.

Let’s look at an example to illustrate the main idea. Suppose you know that your sample is drawn from the normal (μ,1) distribution for an unknown μ, and you are trying to estimate the value of μ. Suppose the sampled values are 52.8, 51.1, 54.2, and 52.5.

That’s a small sample but it carries information. If you had to choose between 32 and 52 as values for μ, which would you choose?

Without any detailed calculations it’s clear that 32 is not a good choice – the normal (32,1) distribution is unlikely to produce values as large as those in the observed sample. If 32 and 52 are your only two choices for μ, you should choose 52.

But of course μ could be any number. To find the best one, you do have to do a calculation.

MLE of μ Based on a Normal (μ,σ2) Sample

Let X1,X2,…,Xn be an i.i.d. normal (μ,σ2) sample. The sample mean is a pretty good estimate of μ, as you know. In this example we will show that it is the maximum likelihood estimate of μ.

What if you want to estimate σ as well? We will tackle that problem at the end of this section. For now, let’s just estimate μ.

The Likelihood Function

The likelihood function is the joint density of the sample evaluated at the observed values, considered as a function of the parameter. That’s a bit of a mouthful but it becomes clear once you see the calculation. The joint density in this example is the product of n normal (μ,σ2) density functions, and hence the likelihood function is

Lik(μ) = n∏i=11√2πσexp(−12(Xi−μσ)2)The quantity Lik(μ) is called the likelihood of the data X1,X2,…,Xn when the mean of the underlying normal distribution is μ. For every fixed μ, Lik(μ) is a function of the sample and hence is a random variable.

You’ll soon see the reason for using the strange notation Lik. Please just accept it for now.

The goal is to find the value of μ that maximizes this likelihood function over all the possible values that μ could be. We don’t yet know if such a maximizing value exists, but let’s try to find it anyway.

To do this we will simplify the likelihood function as much as possible.

Lik(μ) = (1√2πσ)nexp(−12σ2n∑i=1(Xi−μ)2) = Cexp(−12σ2n∑i=1(Xi−μ)2)where C doesn’t depend on μ and thus won’t affect the maximization.

Even in this simplified form, the likelihood function looks difficult to maximize. But as it is a product, we can simplify our calculations still further by taking its log.

The Log Likelihood Function

Not only does the log function turn products into sums, it is an increasing function. Hence the value of μ that maximizes the likelihood function is the same as the value of μ that maximizes the log of the likelihood function.

Let L be the log of the likelihood function, also known as the log likelihood function. You can see the letter l appearing repeatedly in the terminology. Since we’ll be doing most of our work with the log likelihood function, we are calling it L and using Lik for the likelihood function.

L(μ) = log(C)−12σ2n∑i=1(Xi−μ)2The function L looks much more friendly than Lik.

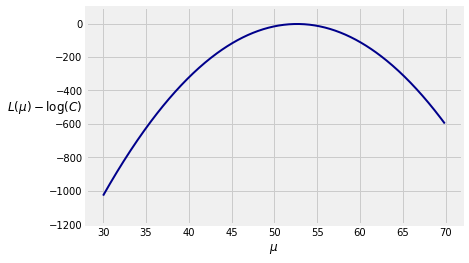

Because log(C) doesn’t affect the maximization, we have defined a function to calculate L−log(C) for the sample 52.8, 51.1, 54.2, and 52.5 drawn from the normal (μ,1) distribution. Remember that we began this section by comparing 32 and 52 as estimates of μ, based on this sample.

sample = make_array(52.8, 51.1, 54.2, 52.5)

def shifted_log_lik(mu):

return (-1/2) * sum((sample - mu)**2)

Here is a graph of the function for μ in the interval (30,70).

The maximizing value of μ looks very close to 52.5. To find exactly where it is, we will find the derivative of L with respect to μ and set that equal to 0.

Derivative of the Log Likelihood Function

Use the Chain Rule and be careful about negative signs.

ddμL(μ) = 22σ2n∑i=1(Xi−μ)Set Equal to 0 and Solve for the MLE

Statisticians have long used the “hat” symbol to denote estimates. So let ˆμ be the MLE of μ. Then ˆμ satisfies an equation:

n∑i=1(Xi−ˆμ) = 0 ⟺ n∑i=1Xi = nˆμ ⟺ ˆμ = 1nn∑i=1Xi = ˉXWe should check that this yields a maximum and not a minimum, but given the answer you will surely accept that it’s a max. You are welcome to take the second derivative of L and check that we do indeed have a maximum.

We have shown that the MLE of μ is the sample mean ˉX, regardless of the population SD σ. In the case of the sample we used for the plot above, ˉX=52.65.

np.mean(sample)

52.650000000000006

You know that the distribution of ˉX is normal with mean μ and variance σ2/n. If you don’t know σ, then if the sample is large you can estimate σ by the SD of the sample and hence construct confidence intervals for μ.

Steps for Finding the MLE

Let’s capture our sequence of steps in an algorithm to find the MLE of a parameter given an i.i.d. sample.

- Write the likelihood of the sample. The goal is to find the value of the parameter that maximizes this likelihood.

- To make the maximization easier, take the log of the likelihood function.

- To maximize the log likelihood with respect to the parameter, take its derivative with respect to the parameter.

- Set the derivative equal to 0 and solve; the solution is the MLE.

Let’s implement this algorithm in another example.

MLE of p Based on a Bernoulli (p) Sample

Let X1,X2,…,Xn be an i.i.d. Bernoulli (p) sample. Our goal is to find the MLE of p.

The random variables are discrete, so the likelihood function is defined as the joint probability mass function evaluated at the sample. To see what this means, let’s start with the example.

Suppose n=5 and the observed sequence of 1’s and 0’s is 01101. The likelihood function at p is the chance of observing this sequence under that value of p:

Lik(p) = (1−p)⋅p⋅p⋅(1−p)⋅p = p3(1−p)2The likelihood depends on the number of 1’s, just as in the binomial probability formula. The combinatorial term is missing because we are observing each element of the sequence.

Now let’s implement our algorithm for finding the MLE.

Step 1: Find the likelihood function.

Let X=X1+X2+…+Xn be the number of 1’s in the sample. The likelihood function is

Lik(p)=pX(1−p)n−XStep 2. Find the log likelihood function.

L(p)=Xlog(p)+(n−X)log(1−p)Step 3. Find the derivative of the log likelihood function.

ddpL(p)=Xp−n−X1−pStep 4. Set equal to 0 and solve for the MLE.

Xˆp−n−X1−ˆp=0Hence

(1−ˆp)X=(n−X)ˆp so X=nˆpTherefore the MLE of p is

ˆp=Xn=1nn∑i=1XiThat is, the MLE of p is the sample proportion of 1’s. To compute this estimate, all you need is the number of 1’s in the sample. You don’t need to see the entire sample as a sequence of 0’s and 1’s.

Because the MLE ˆp is the sample proportion, it is unbiased, has SD √p(1−p)/n, and is asymptotically normal. When n is large you can estimate the SD based on the sample and therefore construct confidence intervals for p.

Properties of the MLE

In the two examples above, the MLE is unbiased and either exactly normal or asymptotically normal. In general, MLEs need not be unbiased, as you will see in an example below. However, under some regularity conditions on the underlying probability distribution or mass function, when the sample is large the MLE is:

- consistent, that is, likely to be close to the parameter

- roughly normal and almost unbiased

Establishing this is outside the scope of this class, but in exercises you will observe these properties through simulation.

Though there is beautiful theory about the asymptotic variance of the MLE, in practice it can be hard to estimate the variance analytically. This can make it hard to find formulas for confidence intervals. However, you can use the bootstrap to estimate the variance: each bootstrapped sample yields a value of the MLE, and you can construct confidence intervals based on the empirical distribution of the bootstrapped MLEs.

MLEs of μ and σ Based on a Normal (μ,σ2) Sample

Let X1,X2,…,Xn be an i.i.d. normal (μ,σ2) sample. We will now find the MLEs of both μ and σ.

The Likelihood Function

We have to think of this as a function of both μ and σ:

Lik(μ,σ) = n∏i=11√2πσexp(−12(Xi−μσ)2) = C⋅1σnn∏i=1exp(−12σ2(Xi−μ)2)where C=1/(√2π)n does not affect the maximization.

The Log Likelihood Function

L(μ,σ) = log(C)−nlog(σ)−12σ2n∑i=1(Xi−μ)2Maximizing the Log Likelihood Function

We will maximize L in two stages:

- First fix σ and maximize with respect to μ.

- Then plug in the maximizing value of μ and maximize the resulting function with respect to σ.

We have already completed the first stage in the first example of this section. For each fixed σ, the maximizing value of μ is ˆμ=ˉX.

So now our job is to find the value ˆσ that maximizes the new function

L∗(σ) = −nlog(σ)−12σ2n∑i=1(Xi−ˉX)2 = −nlog(σ)−12σ2Vwhere V=∑ni=1(Xi−ˉX)2 doesn’t depend on σ. Differentiate with respect to σ; keep track of minus signs and factors of 2.

ddσL∗(σ) = −nσ+1σ3VSet this equal to 0 and solve for the maximizing value ˆσ.

−nˆσ+1ˆσ3V = 0 ⟺ ˆσ2 = Vn = 1nn∑i=1(Xi−ˉX)2Again you should check that this yields a maximum and not a minimum, but again given the answer you will surely accept that it’s a max.

You have shown in exercises that ˆσ2 is not an unbiased estimate of σ2. You have also shown that it is close to unbiased when n is large.

To summarize our result, if X1,X2,…,Xn is an i.i.d. normal (μ,σ2) sample, then the MLEs of μ and σ are given by:

- ˆμ=ˉX

- ˆσ=√ˆσ2 where ˆσ2=1n∑ni=1(Xi−ˉX)2

It is a remarkable fact about i.i.d. normal samples that ˆμ and ˆσ2 are independent of each other even though they are statistics calculated from the same sample. Later in this course you will see why.

Computational Note: MLEs can’t always be derived analytically as easily as in our examples. It’s important to keep in mind that maximizing log likelihood functions can often be intractable without a numerical optimization method. Also, not all likelihood functions have unique maxima.