6.5. Odds Ratios#

Binomial

See More

6.5.1. Consecutive Odds Ratios#

Fix

The idea is to start at the left end of the distribution, with the term

Then we will build up the distribution recursively from left to right, one possible value at a time.

To do this, we have to know how the probabilities of consecutive values are related to each other. For

These ratios help us calculate

and so on.

Even though we already have a formula for the binomial probabilities, building the distribution using consecutive ratios is better computationally and also helps us understand the shape of the distribution.

See More

6.5.2. Binomial Consecutive Odds Ratios#

How is this more illuminating than plugging into the binomial formula? To see this, fix

Notice that the formulas for

Quick Check

In the binomial scipy or combinatorics) to find

Answer

Multiply by

6.5.3. Shapes of Binomial Histograms#

Now observe that comparing

Note also that the form

tells us the the ratios are a decreasing function of

This implies that once

That is why binomial histograms are either non-increasing or non-decreasing, or they go up and come down. But they can’t look like waves on the seashore. They can’t go up, come down, and go up again.

See More

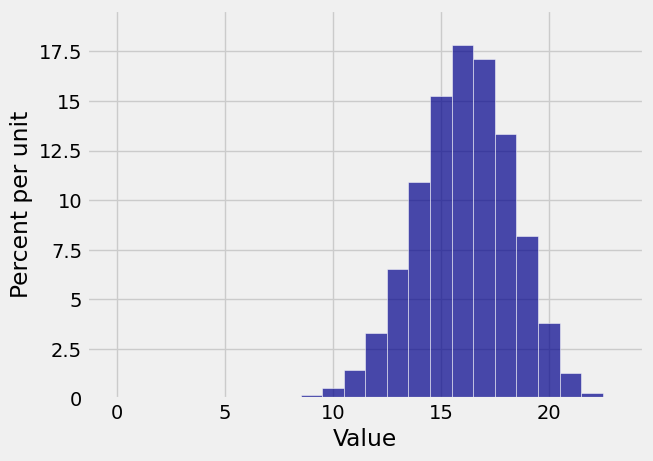

Let’s visualize this for a

n = 23

p = 0.7

k = range(n+1)

bin_23_7 = stats.binom.pmf(k, n, p)

bin_dist = Table().values(k).probabilities(bin_23_7)

Plot(bin_dist)

# It is important to define k as an array here,

# so you can do array operations

# to find all the ratios at once.

k = np.arange(1, n+1, 1)

((n - k + 1)/k)*(p/(1-p))

array([ 53.66666667, 25.66666667, 16.33333333, 11.66666667,

8.86666667, 7. , 5.66666667, 4.66666667,

3.88888889, 3.26666667, 2.75757576, 2.33333333,

1.97435897, 1.66666667, 1.4 , 1.16666667,

0.96078431, 0.77777778, 0.61403509, 0.46666667,

0.33333333, 0.21212121, 0.10144928])

What Python is helpfully telling us is that the invisible bar at 1 is 53.666… times larger than the even more invisible bar at 0. The ratios decrease after that but they are still bigger than 1 through

6.5.4. Mode of the Binomial#

A mode of a discrete distribution is a possible value that has the highest probability. There may be more than one such value, so there may be more than one mode.

We have seen that once the ratio

Let

That is,

which is equivalent to

We have shown that for all

Therefore the peak of the histogram is at the largest

So the integer part of

Because the odds ratios are non-decreasing in

The mode of the binomial

To see that this is consistent with what we observed in our numerical example above, let’s calculate

(n+1) * p

16.799999999999997

The integer part of

But in fact,

In fact you don’t have to worry when