18.3. The Gamma Family#

You have seen in exercises that a non-negative random variable

Here

is the Gamma function applied to

As you have shown, the key fact about the Gamma function is the recursion

which implies in particular that

You have put all this together to show that

You have observed that the square of a standard normal variable has the gamma

18.3.1. The Rate

For fixed

SciPy calls

Quick Check

Suppose

Answer

gamma

18.3.2. The Shape Parameter

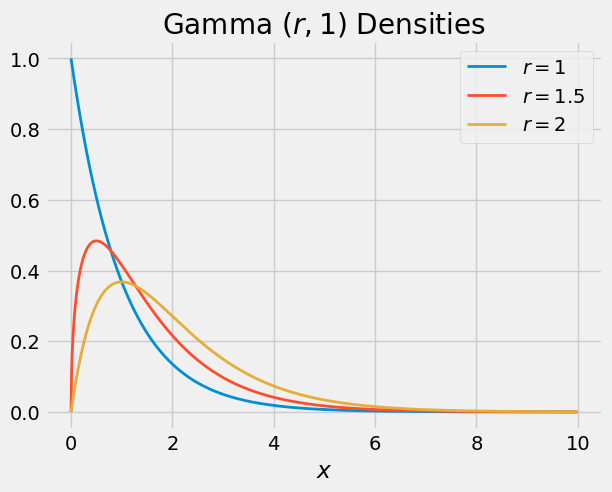

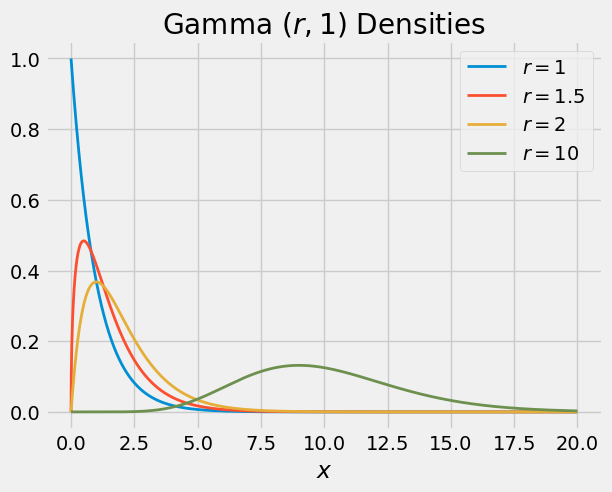

Here are the graphs of the gamma

When

You can see why the gamma family is used for modeling right-skewed distributions. However, when

18.3.3. Sums of Independent Gamma Variables with the Same Rate#

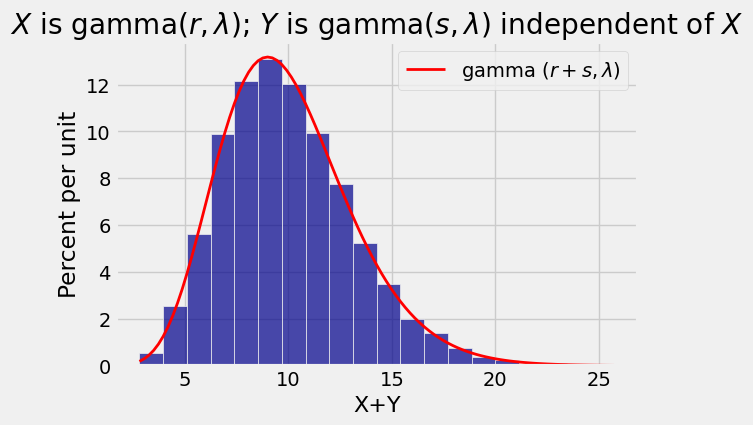

If

Note that for the result to apply, the rate parameter has to be the same for

We will prove this result in the next chapter along with the corresponding result for sums of independent normal variables. For now, let’s test out the result by simulation just as we did with the sums of normals. The first three lines in the cell below set the values of

# Change these three parameters as you wish.

lam = 1

r = 3

s = 7

# Leave the rest of the code alone.

x = stats.gamma.rvs(r, scale=1/lam, size=10000)

y = stats.gamma.rvs(s, scale=1/lam, size=10000)

w = x+y

Table().with_column('X+Y', w).hist(bins=20)

t = np.arange(min(w), max(w)+0.1, (max(w) - min(w))/100)

dens = stats.gamma.pdf(t, r+s, scale=1/lam)

plt.plot(t, dens, color='red', lw=2, label='gamma $(r+s, \lambda)$')

plt.legend()

plt.title('$X$ is gamma$(r, \lambda)$; $Y$ is gamma$(s, \lambda)$ independent of $X$');

Quick Check

If

Answer

gamma

See More

18.3.4. Integer Shape Parameter#

One of the two most important branches of the gamma family consists of gamma distributions that have an integer as the shape parameter.

Suppose

By the fact we observed about sums of independent gamma variables, for all integers

You can now see why the gamma

Gamma distributions with integer shape parameter are a fundamental part of a stochastic process called a Poisson process which you will examine in exercises.

The other important branch of the gamma family is the topic of the next section.