7.1. Poisson Distribution#

We know that when

where

The terms in the approximation are proportional to terms in the series expansion of

A little care is required before we go further. First, we must state the additivity axiom of probability theory in terms of countably many outcomes:

If events

This is called the countable additivity axiom, in contrast to the finite additivity axiom we have thus far assumed. It doesn’t follow from finite additivity, but of course finite additivity follows from it.

In this course, we will not go into the technical aspects of countable additivity and the existence of probability functions that satisfy the axioms on the spaces that interest us. But those technical aspects do have to be studied before you can develop a deeper understanding of probability theory. If you want to do that, a good start is to take Real Analysis and then Measure Theory.

While in this course, you don’t have to worry about it. Just assume that all our work is consistent with the axioms.

Here is our first infinite valued distribution.

See More

7.1.1. Poisson Probabilities#

A random variable

The terms are proportional to the terms in the infinte series expansion of

The constant of proportionality is

Keep in mind that the Poisson is a distribution in its own right. It does not have to arise as a limit, though it is sometimes helpful to think of it that way. Poisson distributions are often used to model counts of rare events, not necessarily arising out of a binomial setting.

Quick Check

The number of raisins in a cookie has the Poisson

Answer

7.1.2. An Interpretation of the Parameter#

To understand the parameter prob140 library considers it a Distribution object.

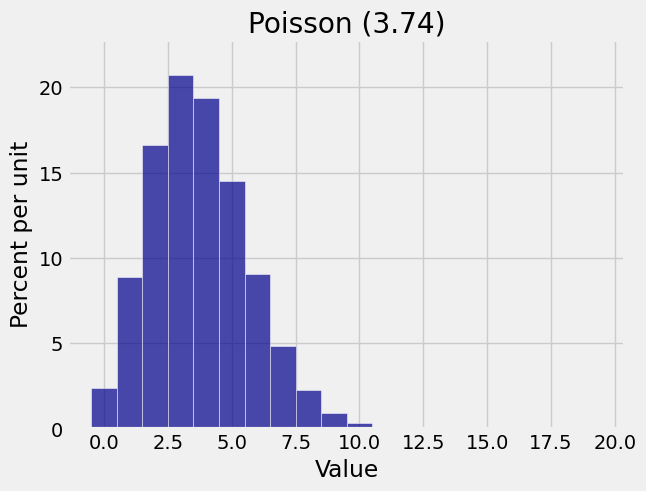

mu = 3.74

k = range(20)

poi_probs_374 = stats.poisson.pmf(k, mu)

poi_dist_374 = Table().values(k).probabilities(poi_probs_374)

Plot(poi_dist_374)

plt.title('Poisson (3.74)');

The mode is 3. To find a formula for the mode, follow the process we used for the binomial: calculate the consecutive odds ratios, notice that they are decreasing, and see where they cross 1. This is left to you as an exercise. Your calculations should conclude the following:

The mode of the Poisson distribution is the integer part of

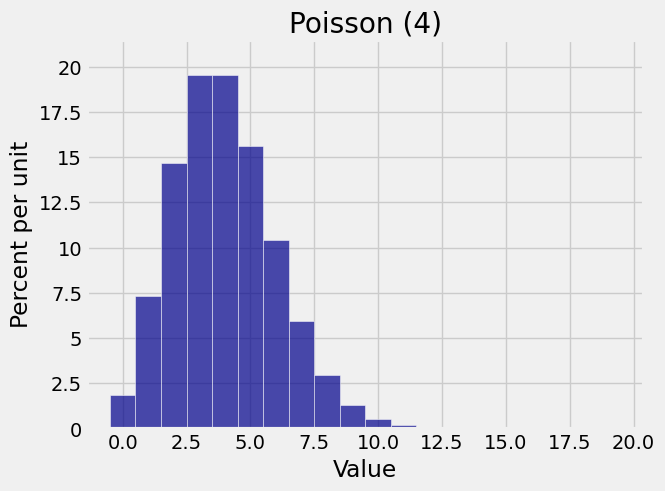

mu = 4

k = range(20)

poi_probs_4 = stats.poisson.pmf(k, mu)

poi_dist_4 = Table().values(k).probabilities(poi_probs_4)

Plot(poi_dist_4)

plt.title('Poisson (4)');

In later chapters we will learn a lot more about the parameter

See More

7.1.3. Sums of Independent Poisson Variables#

Let

To prove this, first notice that the possible values of

by the binomial expansion of

One important application of this result is that if

Quick Check

In a grocery store line, the number of people younger than 25 has the Poisson

Answer