15.2. The Meaning of Density#

When we work with a discrete random variable

What is the analog of

15.2.1. If

If

“But

The fact that the chance of any single value is 0 actually reduces some bookkeeping. When we are calculating probabilities involving random variables that have densities, we don’t have to worry about whether we should or should not include endpoints of intervals. The chance of each endpoint is 0, so for example,

Being able to drop the equal sign like this is a major departure from calculations involving discrete random variables;

See More

15.2.2. An Infinitesimal Calculation#

In the theory of Riemann integration, the area under a curve is calculated by discrete approximation. The interval on the horizontal axis is divided into tiny little segments. Each segment becomes the base of a very narrow rectangle with a height determined by the curve. The total area of all these rectangular slivers is an approximation to the integral. As you make the slivers narrower, the sum approaches the area under the curve.

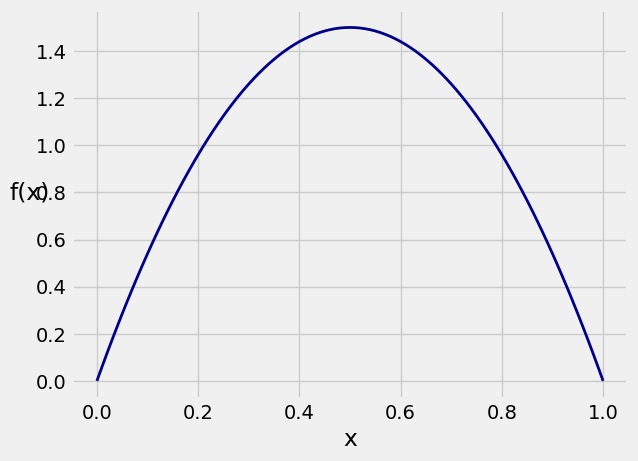

Let’s examine this in the case of the density we used as our example in the previous section:

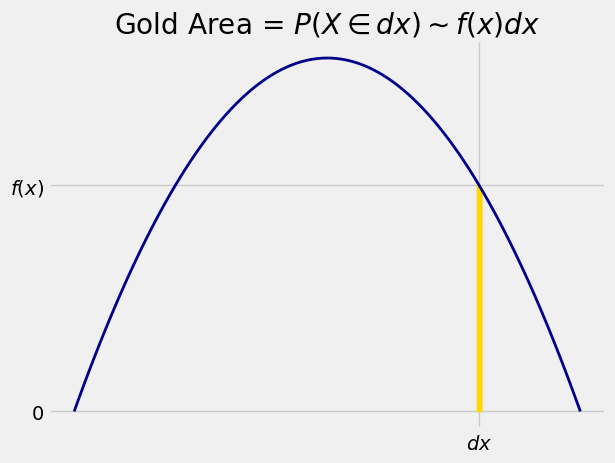

Here is one of those narrow slivers.

We will now set up some notation that will be used repeatedly in the course.

a tiny interval around

the length of the tiny interval

Now

In this notation, the area of the gold sliver is essentially that of a rectangle with height

where as usual

We have seen that

This gives us an important analogy. When

When

The calculus notation is clever as well as powerful. It involves two analogies:

the integral is a continuous version of the sum

Quick Check

A random variable

(a) For all

(b) For all

(c) For all

(d) For all

Answer

False, False, True, True

Quick Check

A random variable

Answer

All three are equal

15.2.3. Probability Density#

We can rewrite

The function

Let’s take another look at the graph of

If you simulate multiple independent copies of a random variable that has this density (exactly how to do that will be the subject of the next lab), then for example the simulated values will be more crowded around 0.5 than around 0.2.

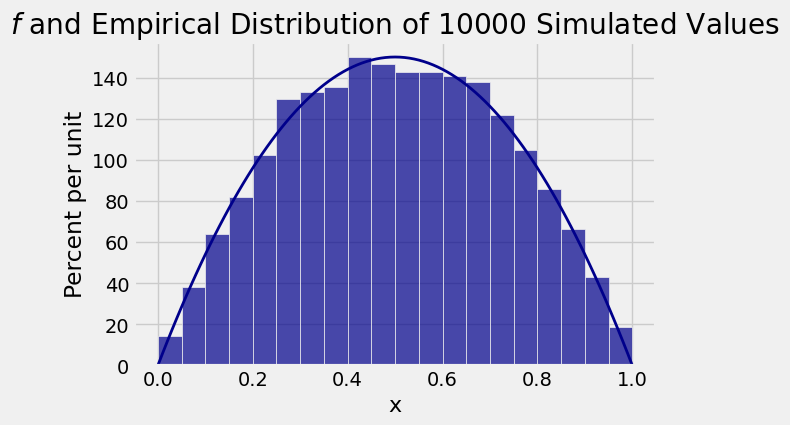

The function simulate_f takes the number of copies as its argument and displays a histogram of the simulated values overlaid with the graph of

simulate_f(10000)

The distribution of 10,000 simulated values follows

Compare the vertical scale of the histogram above with the vertical scale of the graph of

Now you have a better understanding of why all histograms in Data 8 are drawn to the density scale, with heights calculated as

so that the units of height are “percent per unit on the horizontal axis”.

Not only does this way of drawing histograms allow you to account for bins of different widths, as discussed in Data 8, it also leads directly to probability densities of random variables. You can think of the density curve as what the empirical histogram of the simulated values would look like if you had infinitely many simulations and infinitely narrow bins.