15.3. Expectation#

See More

Let

Write a generic value of

Apply the function

Weight

“Sum” over all

The expectation is

Technical Note: We must be careful here as

For a general

If it is finite then there is a theorem that says

Non-technical Note: In almost all of our examples, we will not be faced with questions about the existence of integrals. For example, if the set of possible values of

All the properties of means, variances, and covariances that we proved for discrete variables are still true. The proofs need to be rewritten for random variables with densities, but we won’t take the time to do that. Just use the properties as you did before. The Central Limit Theorem holds as well.

Quick Check

Answer

15.3.1. Uniform

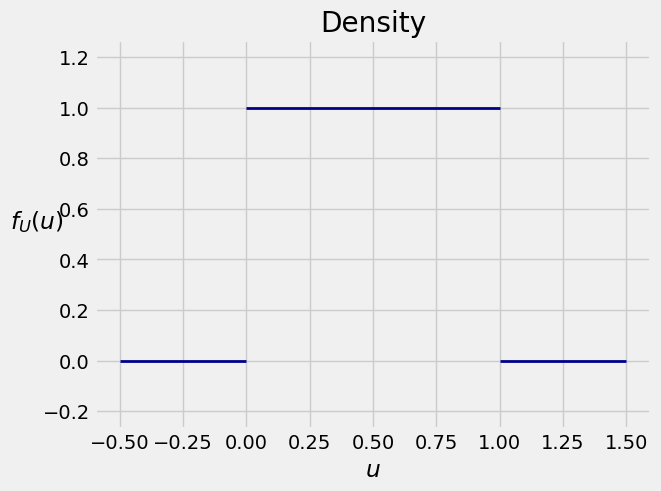

The random variable

The area under

Equivalently, the cdf of

The expectation

For the variance, you do have to integrate. By the formula for expectation given at the start of this section,

15.3.2. Uniform

Fix

So if

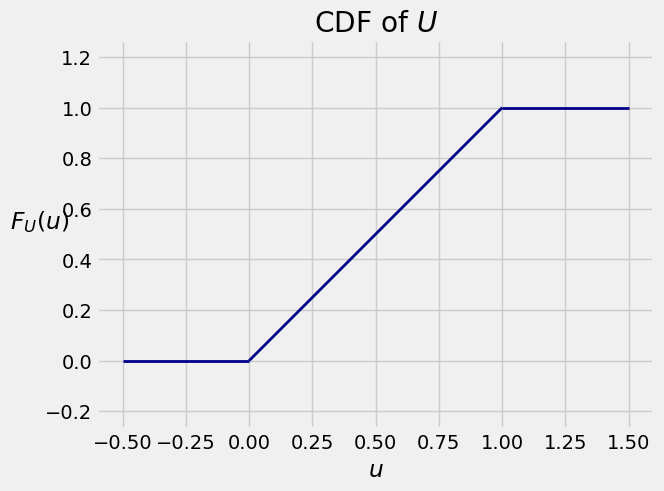

and 0 elsewhere. Probabilities are still relative lengths, so the cdf of

The expectation and variance of

Step 1:

Step 2:

Step 3:

Now

which is the midpoint of

Quick Check

(a) Let

(b) Let

Answer

(a)

(b)

15.3.3. Example: Random Discs#

A screen saver chooses a random radius uniformly in the interval

Question 1. Let

Answer. Let

np.pi * (4/12 + 1)

4.1887902047863905

Question 2. Let

Answer. Let

sd_rbar = ((4/12)**0.5)/(100**0.5)

sd_rbar

0.057735026918962574

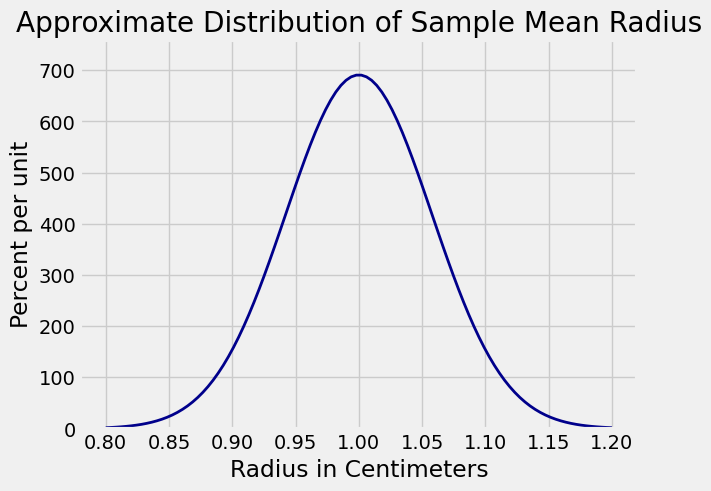

By the Central Limit Theorem, the distribution of Plot_norm.

Plot_norm((0.8, 1.2), 1, sd_rbar)

plt.xlabel('Radius in Centimeters')

plt.title('Approximate Distribution of Sample Mean Radius');

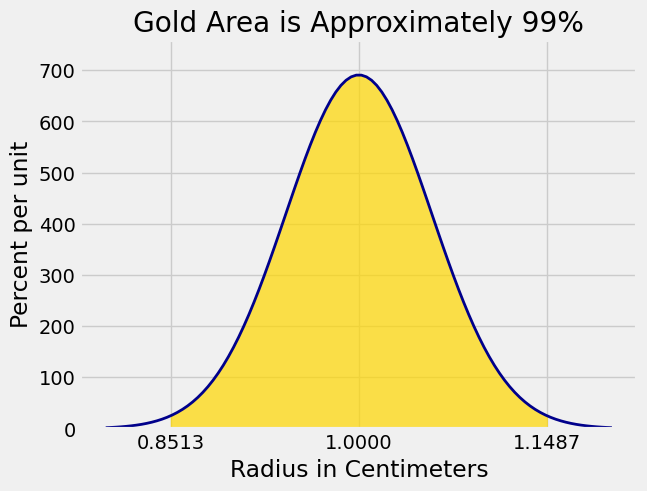

We are looking for

z = stats.norm.ppf(0.995)

z

2.5758293035489004

c = z*sd_rbar

c

0.14871557417904838

We can now get the endpoints of the interval. The graph below shows the corresponding area of 99%.

1-c, 1+c

(0.85128442582095165, 1.1487155741790485)

Plot_norm((0.8, 1.2), 1, sd_rbar, left_end = 1-c, right_end = 1+c)

plt.xticks([1-c, 1, 1+c])

plt.xlabel('Radius in Centimeters')

plt.title('Gold Area is Approximately 99%');

Quick Check

Let

Answer

Roughly normal, mean