15.1. Density and CDF#

See More

Let

Then

In the next section we will discuss the reason behind the name. For now, imagine the graph of

Quick Check

Consider the function

Answer

Non-negative, total area under the graph is 1

As an example, the function

is a density. It is easy to check by calculus that it integrates to 1.

Note: The calculus used in this text is very straightforward. You should be able to do it easily by hand. Later in this chapter we will give you some Python tools for calculus. We will also show how understanding probability can help us do calculus quickly.

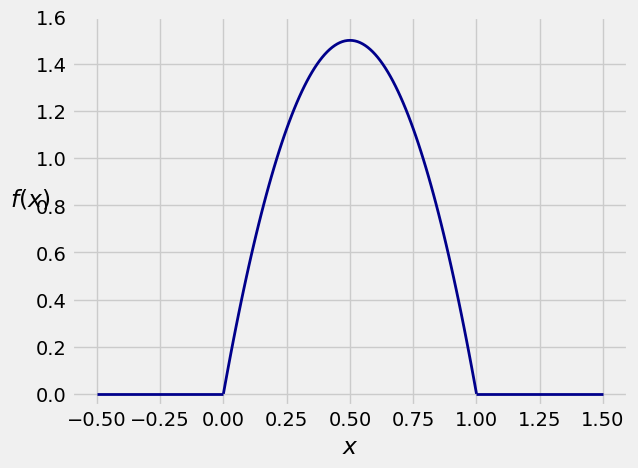

Here is a graph of the function

15.1.1. Density is Not the Same as Probability#

In the example above,

Then what are they? We’ll study that in the next section. In this section we will see that we can work with densities just as we did with the normal curve.

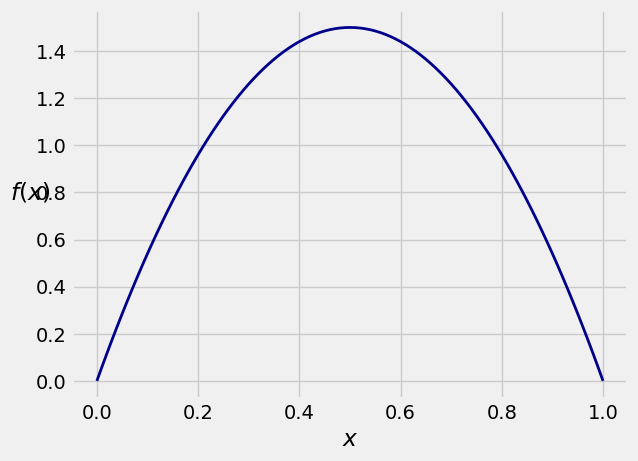

First, a labor-saving device: If

And we will draw the graph of

15.1.2. Areas are Probabilities#

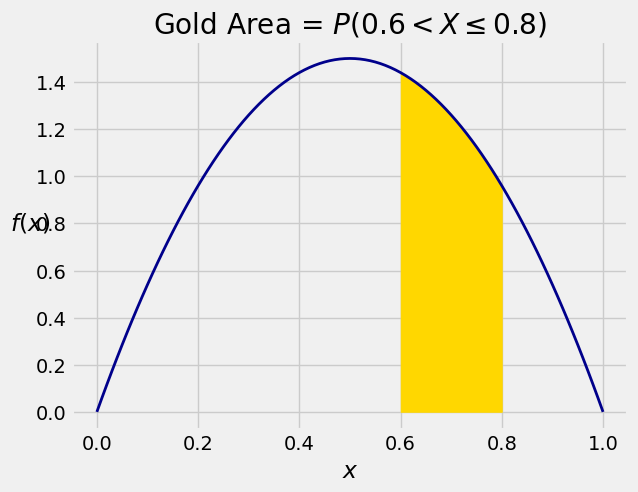

A random variable

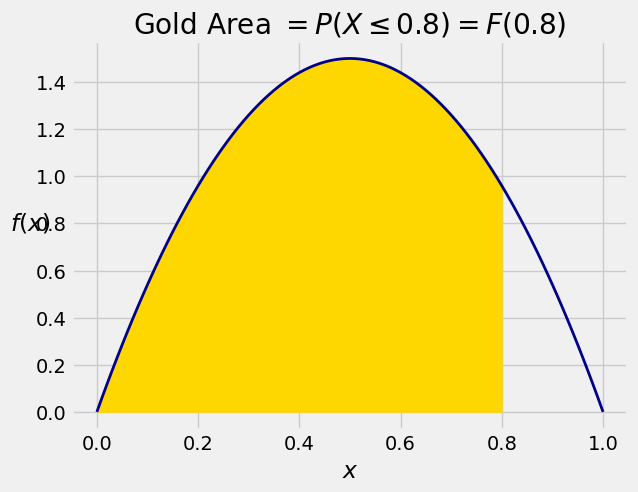

This integral is the area between

The area is

Quick Check

Let

Answer

See More

15.1.3. Cumulative Distribution Function (CDF)#

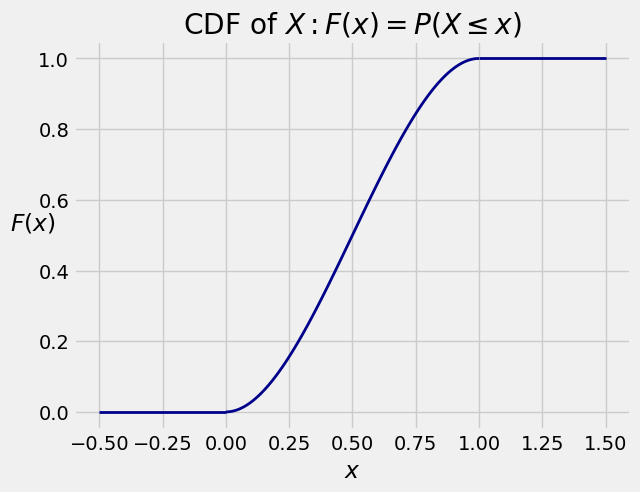

The cdf of

You are already familiar with the definition

In our example, the only possible values of the random variable

In terms of the graph of the density,

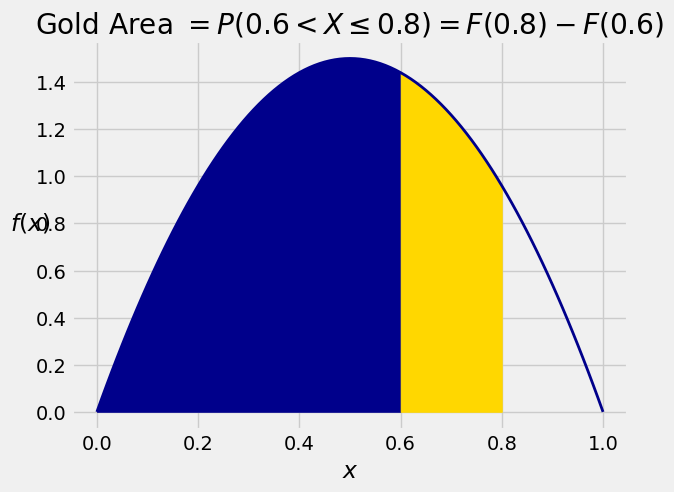

As before, the cdf can be used to find probabilities of intervals. For every pair

That’s the same as the answer we got earlier in the section by integrating the density between 0.6 and 0.8.

By the Fundamental Theorem of Calculus, the density and cdf can be derived from each other:

You can use whichever of the two functions is more convenient in a particular application.

Also keep in mind that every cdf