13.3. Sums of Independent Variables#

After the dry, algebraic discussion of the previous section it is a relief to finally be able to compute some variances.

See More

13.3.1. The Variance of a Sum#

Let

The variance of the sum is

We say that the variance of the sum is the sum of all the variances and all the covariances.

The first sum has

The second sum has

Since

13.3.2. Sum of Independent Random Variables#

If

Therefore if

Thus for independent random variables

When the random variables are i.i.d., this simplifies even further.

See More

13.3.3. Sum of an IID Sample#

Let

Let

This implies that as the sample size

Quick Check

Suppose the sizes of

(a) Pick one of the following values for

(b) Pick one of the following values for

Answer

(a)

(b)

Here is an important application of the formula for the variance of an i.i.d. sample sum.

13.3.4. Variance of the Binomial#

Let

where

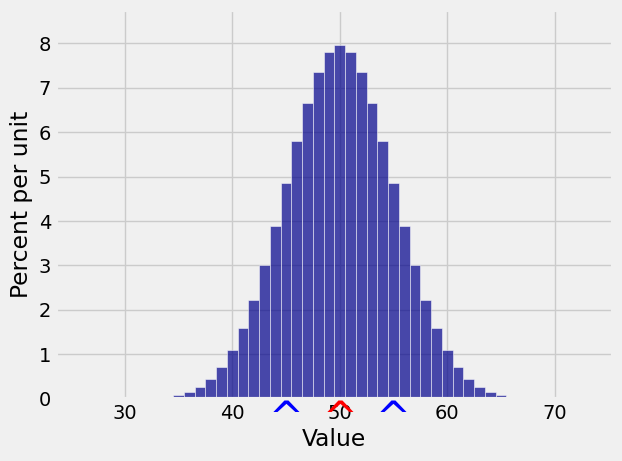

For example, if

Here is the distribution of

k = np.arange(25, 75, 1)

binom_probs = stats.binom.pmf(k, 100, 0.5)

binom_dist = Table().values(k).probabilities(binom_probs)

Plot(binom_dist, show_ev=True, show_sd=True)

Quick Check

A die is rolled

Answer

Expectation

See More

13.3.5. Variance of the Poisson, Revisited#

We showed earlier that if

One way in which a Poisson

Now let’s compare the standard deviations. The standard deviation of the binomial is

But