16.3. Simulation via the CDF#

How do you generate a random variable that has a specified distribution? The answer is quite remarkable and is used by computational systems to generate values of random variables whose distribution you have specified.

Our goal is to generate a value of a random variable that has a particular distribution. Let

The statement below describes the process. Note that because we have assumed

Generate

Create a random variable

Done! The random variable

To prove the result, remember that the cdf

This is an extremely important result for computation as well as theory. It says that computing systems should pay great attention to the quality of their uniform

For example, here is a way to generate a normal

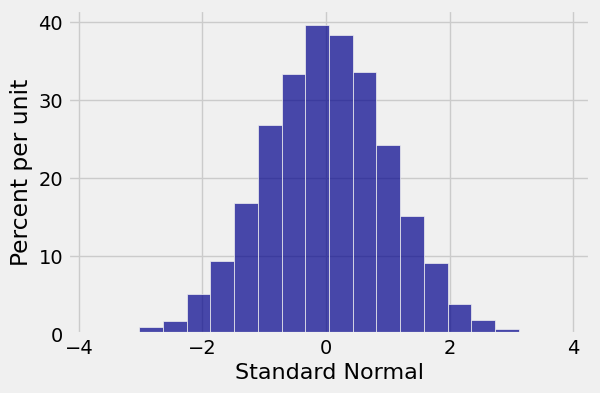

Start with

By our result above,

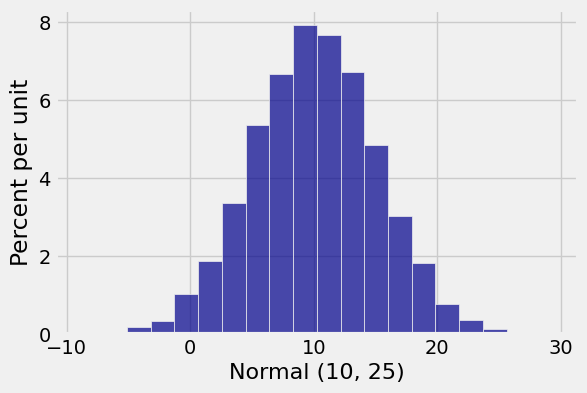

By linear transformation facts,

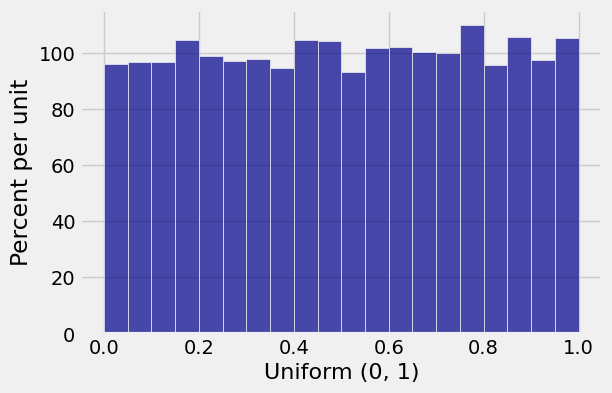

Here is the plan in action, in the case stats.uniform.rvs generates uniform size specifies how many numbers to generate.

uniforms = stats.uniform.rvs(size=10000)

standard_normals = stats.norm.ppf(uniforms)

normal_10_25 = 5*standard_normals + 10

results = Table().with_columns(

'Uniform (0, 1)', uniforms,

'Standard Normal', standard_normals,

'Normal (10, 25)', normal_10_25

)

results.hist('Uniform (0, 1)', bins=20)

results.hist('Standard Normal', bins=20)

results.hist('Normal (10, 25)', bins=20)

You can repeat the process for any distribution you want to simulate.

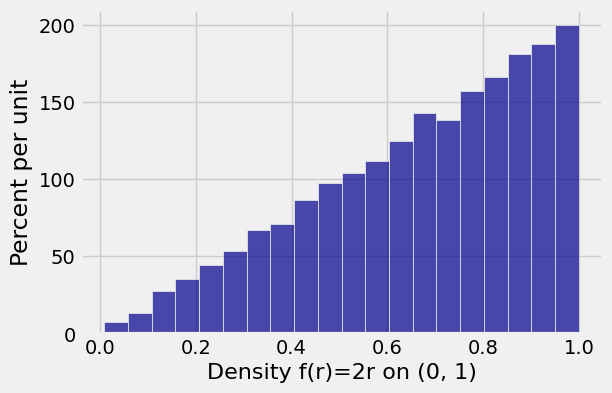

For example, to generate random variables whose density is

Then find the inverse of

For

Then apply

Here is the plan in action, using the uniform random numbers generated above.

results = results.with_columns(

'Density f(r)=2r on (0, 1)', uniforms ** 0.5

)

results.hist('Density f(r)=2r on (0, 1)', bins=20)