6.6. The Law of Small Numbers#

The consecutive odds ratios of the binomial

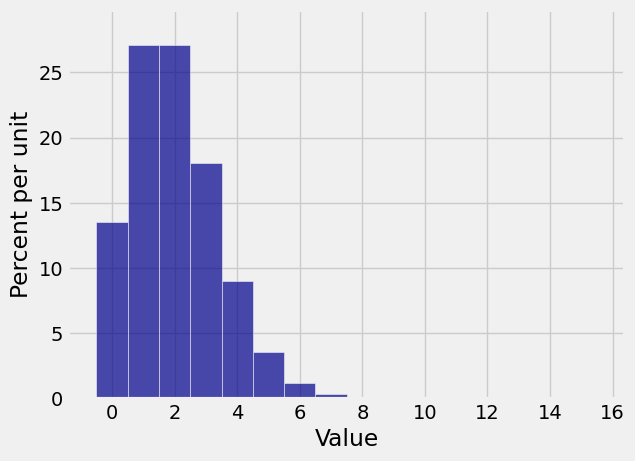

As an example, here is the binomial

n = 1000

p = 2/1000

k = np.arange(16)

binom_probs = stats.binom.pmf(k, n, p)

binom_dist = Table().values(k).probabilities(binom_probs)

Plot(binom_dist)

Though the possible values of the number of successes in 1000 trials can be anywhere between 0 and 1000, the probable values are all rather small because

Since the histogram is all scrunched up near 0, only very few bars have noticeable probability. It really should be possible to find or approximate the chances of the corresponding values by a simpler calculation than the binomial formula.

To see how to do this, we will start with

6.6.1. Approximating

Remember that

There are two reasons for the condition that

To ensure that

To ensure that

Let

Then

One way to see the limit is to appeal to our familiar exponential approxmation:

when

See More

6.6.2. Approximating

In general, for fixed

when

For large

By induction, this implies the following approximation for each fixed

if

See More

6.6.3. Poisson Approximation to the Binomial#

Let

This is called the Poisson approximation to the binomial. The parameter of the Poisson distribution is

The distribution is named after its originator, the French mathematician Siméon Denis Poisson (1781-1840).

Quick Check

Let

Answer

The terms in the approximation are proportional to the terms in the series expansion of

The expansion is infinite, but we are only going up to a finite (though large) number of terms

We’ll get to that in a later section. For now, let’s see if the approximation we derived is any good.

6.6.4. Poisson Probabilities in Python#

Use stats.poisson.pmf just as you would use stats.binomial.pmf, but keep in mind that the Poisson has only one parameter.

Suppose

stats.binom.pmf(3, 1000, 2/1000)

0.18062773231732265

The approximating Poisson distribution has parameter

stats.poisson.pmf(3, 2)

0.18044704431548356

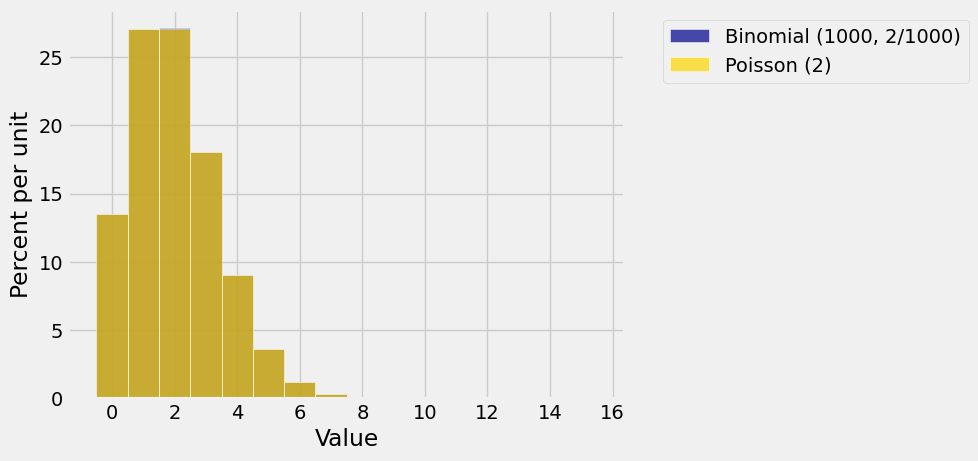

Not bad. To compare the entire distributions, first create the two distribution objects:

k = range(16)

bin_probs = stats.binom.pmf(k, 1000, 2/1000)

bin_dist = Table().values(k).probabilities(bin_probs)

poi_probs = stats.poisson.pmf(k, 2)

poi_dist = Table().values(k).probabilities(poi_probs)

The prob140 function that draws overlaid histograms is called Plots (note the plural). The syntax has alternating arguments: a string label you provide for a distribution, followed by that distribution, then a string label for the second distribution, then that distribution.

Plots('Binomial (1000, 2/1000)', bin_dist, 'Poisson (2)', poi_dist)

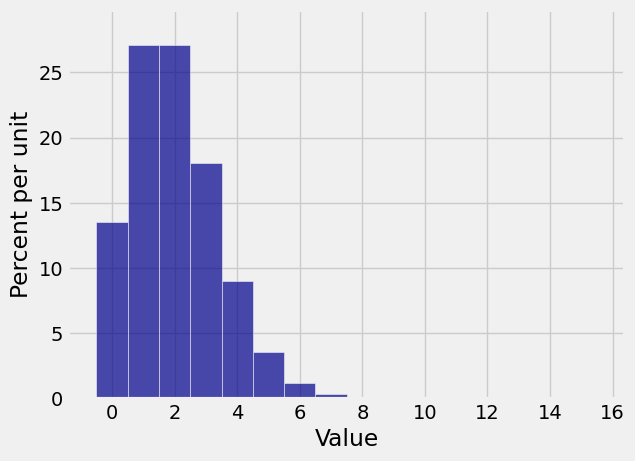

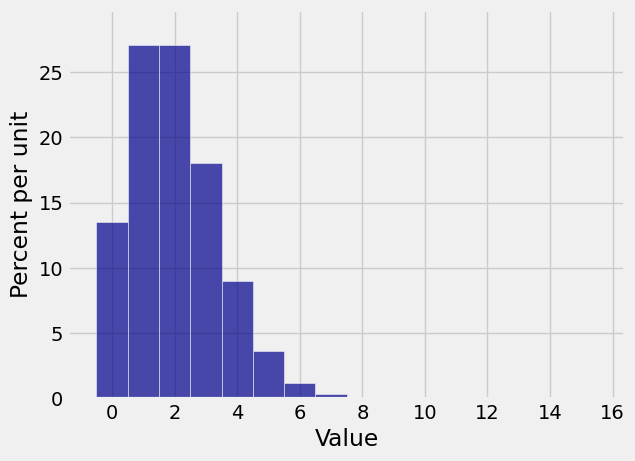

Does it look as though there is only one histogram? That’s because the approximation is great! Here are the two histograms individually.

Plot(bin_dist)

Plot(poi_dist)

In lab, you will use total variation distance to get a bound on the error in the approximation.

A reasonable question to ask at this stage is, “Well that’s all very nice, but why should I bother with approximations when I can just use Python to compute the exact binomial probabilities using stats.binom.pmf?”

Part of the answer is that if a function involves parameters, you can’t understand how it behaves by just computing its values for some particular choices of the parameters. In the case of Poisson probabilities, we will also see shortly that they form a powerful distribution in their own right, on an infinite set of values.