8.4. Additivity#

Calculating expectation by plugging into the definition works in simple cases, but often it can be cumbersome or lack insight. The most powerful result for calculating expectation turns out not to be the definition. It looks rather innocuous:

8.4.1. Additivity of Expectation#

Let

Before we look more closely at this result, note that we are assuming that all the expectations exist; we will do this throughout in this course.

And now note that there are no assumptions about the relation between

See More

Additivity follows easily from the definition of

Thus a “value of

Sum the two sides over all

Quick Check

Let

(a) Find

(b) Find

Answer

(a)

(b)

By induction, additivity extends to any finite number of random variables. If

regardless of the dependence structure of

If you are trying to find an expectation, then the way to use additivity is to write your random variable as a sum of simpler variables whose expectations you know or can calculate easily.

8.4.2.

Let

Now

We will use this fact later when we study the variability of

It is worth noting that it is not easy to calculate

is not an easy sum to simplify.

8.4.3. Sample Sum#

Let

Then, regardless of whether the sample was drawn with or without replacement, each

So, regardless of whether the sample is drawn with or without replacement,

We can use this to estimate a population mean based on a sample mean.

8.4.4. Unbiased Estimator#

Suppose a random variable

The bias of

If the bias of an estimator is

If an estimator is unbiased, and you use it to generate estimates repeatedly and independently, then in the long run the average of all the estimates is equal to the parameter being estimated. On average, the unbiased estimator is neither higher nor lower than the parameter. That’s usually considered a good quality in an estimator.

In practical terms, if a data scientist wants to estimate an unknown parameter based on a random sample

Recall from Data 8 that a statistic is a number computed from the sample. In other words, a statistic is a numerical function of

Constructing an unbiased estimator of a parameter

8.4.5. Unbiased Estimators of a Population Mean#

As in the sample sum example above, let

Then, regardless of whether the draws were made with replacement or without,

Thus the sample mean is an unbiased estimator of the population mean.

It is worth noting that

But it seems clear that using the sample mean as the estimator is better than using just one sampled element, even though both are unbiased. This is true, and is related to how variable the estimators are. We will address this later in the course.

Quick Check

Let

Answer

Yes

See More

8.4.6. First Unbiased Estimator of a Maximum Possible Value#

Suppose we have a sample

How can we use the sample to construct an unbiased estimator of

In other words, we have to construct a statistic that has expectation

Each

The expectation of each of the uniform variables is

Clearly,

But because

Remember that our job is to create a function of the sample

Start by inverting the linear function, that is, by isolating

This tells us what we have to do to the sample

We should just use the statistic

Quick Check

In the setting above, what is the bias of

Answer

8.4.7. Second Unbiased Estimator of the Maximum Possible Value#

The calculation above stems from a problem the Allied forces faced in World War II. Germany had a seemingly never-ending fleet of Panzer tanks, and the Allies needed to estimate how many they had. They decided to base their estimates on the serial numbers of the tanks that they saw.

Here is a picture of one from Wikipedia.

Notice the serial number on the top left. When tanks were disabled or destroyed, it was discovered that their parts had serial numbers too. The ones from the gear boxes proved very useful.

The idea was to model the observed serial numbers as random draws from

The model was that the draws were made at random without replacement from the integers 1 through

In the example above, we constructed the random variable

The Allied statisticians instead started with

The sample maximum

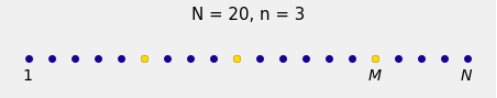

To correct for this, the Allied statisticians imagined a row of

There are

From these, we take a simple random sample of size

The remaining

The

A key observation is that because of the symmetry of simple random sampling, the lengths of all four gaps have the same distribution.

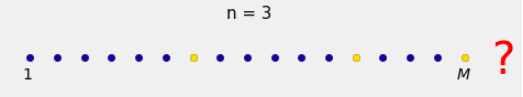

But of course we don’t get to see all the gaps. In the sample, we can see all but the last gap, as in the figure below. The red question mark reminds you that the gap to the right of

If we could see the gap to the right of

Since we can see all of the spots and their colors up to and including

We can see

So the Allied statisticians decided to improve upon

By algebra, this estimator can be rewritten as

Is

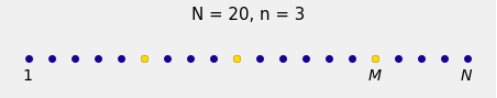

Here once again is the visualization of what’s going on.

Let

There are

So

Recall that the Allied statisticians’ estimate of

Now

Thus the augmented maximum

Quick Check

A gardener in Berkeley has 23 blue flower pots in a row. She picks a simple random sample of 5 of them and colors the selected pots gold. What is the expected number of blue flower pots at the end of the row?

Answer

8.4.8. Which Estimator to Use?#

The Allied statisticians thus had two unbiased estimators of

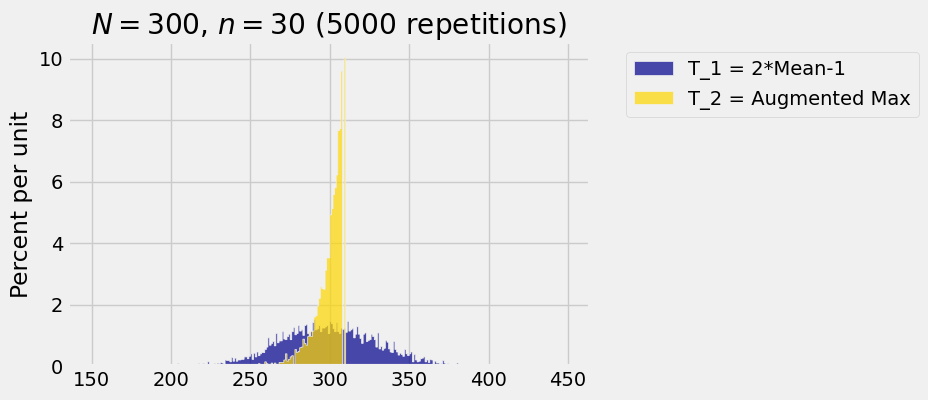

We will quantify this later in the course. For now, here is a simulation of distributions of the two estimators in the case

You can see why

Both are unbiased. So both the empirical histograms are balanced at around

The emipirical distribution of

For a recap, take another look at the accuracy table of the Allied statisticians’ estimator