17.1. Probabilities and Expectations#

See More

A function

If you think of

Think of probabilities as volumes under the surface, and define

That is, the chance that the random point

This is a two-dimensional analog of the fact that probabilities involving a single continuous random variable can be thought of as areas under the density curve.

Quick Check

Random variables

(i) Could be any non-negative number

(ii) Has to be in

(iii) Has to be in

(iv) None of the above

Answer

(ii)

See More

17.1.1. Infinitesimals#

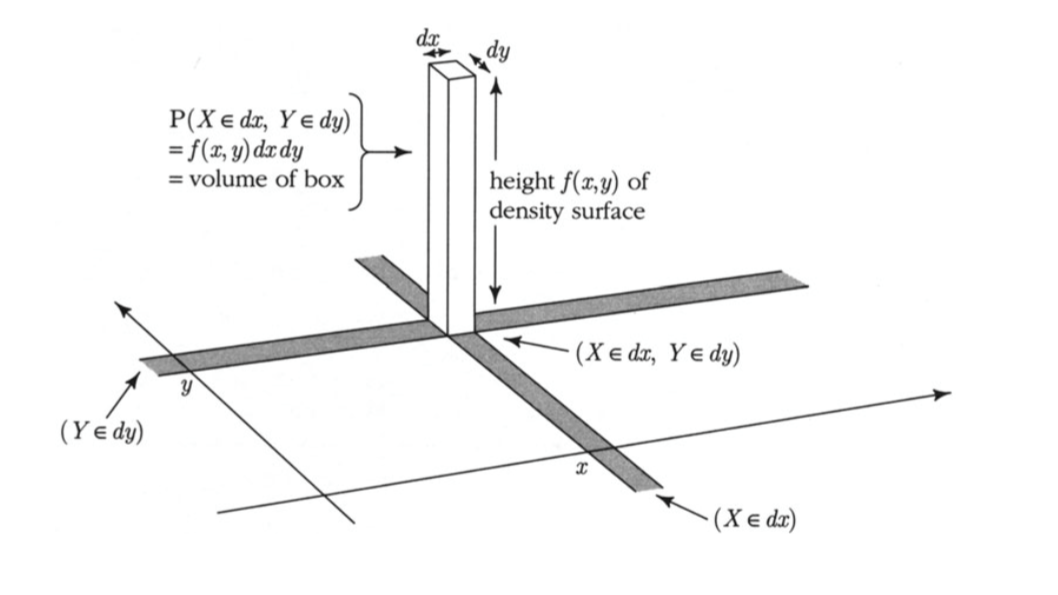

Also analogous is the interpretation of the joint density as part of the calculation of the probability of an infinitesimal region.

The infinitesimal region is a tiny rectangle in the plane just around the point

The infinitesimal region is a tiny rectangle in the plane just around the point

Thus for all

and the joint density measures probability per unit area:

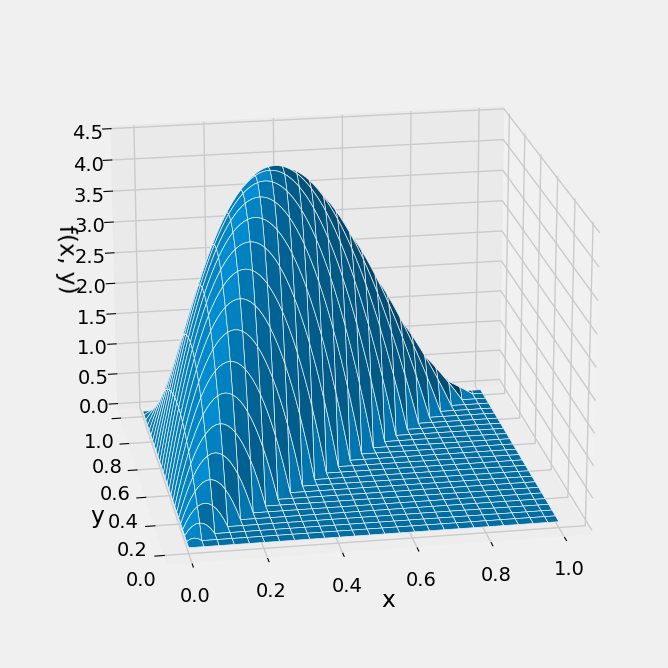

An example will help us visualize all this. Let

For now, just assume that this is a joint density, that is, it integrates to 1. Let’s first take a look at what the surface looks like.

17.1.2. Plotting the Surface#

To do this, we will use a 3-dimensional plotting routine. First, we define the joint density function. For use in our plotting routine, this function must take

def joint(x,y):

if y < x:

return 0

else:

return 120 * x * (y-x) * (1-y)

Now we will call Plot_3d to plot the surface. The arguments are the limits on the rstride and cstride that determine how many grid lines to use. Larger numbers correspond to less frequent grid lines.

Plot_3d(x_limits=(0,1), y_limits=(0,1), f=joint, cstride=4, rstride=4)

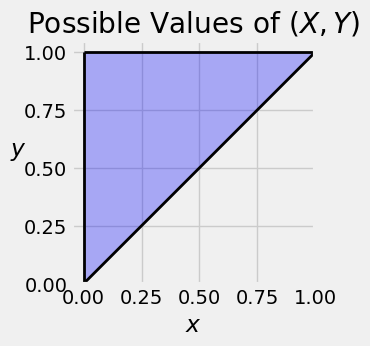

The surface has level 0 in the lower right hand triangle because it is not possible for the point

The possible values of

See More

17.1.3. The Total Volume Under the Surface#

The function

To set up the double integral over the entire region of possible values, notice that for each fixed value of

We will first fix

17.1.3.1. By SymPy#

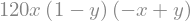

To use SymPy we must create two symbolic variables. As our variables are positive, we can specify that as well. Then we can assign the expression that defines the function to the name f. This specification doesn’t say that

x = Symbol('x', positive=True)

y = Symbol('y', positive=True)

f = 120*x*(y-x)*(1-y)

f

Displaying the double integral requires a call to Integral that specifies the inner integral first and then the outer. The call says:

The function being integrated is

The inner integral is over the variable

The outer integral is over the variable

Integral(f, (x, 0, y), (y, 0, 1))

To evaluate the integral, use doit():

Integral(f, (x, 0, y), (y, 0, 1)).doit()

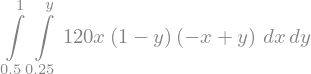

Quick Check

For

Answer

See More

17.1.4. Probabilities as Volumes#

Probabilities are volumes under the joint density surface. In other words, they are double integrals of the function SymPy.

17.1.5. Example 1#

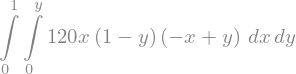

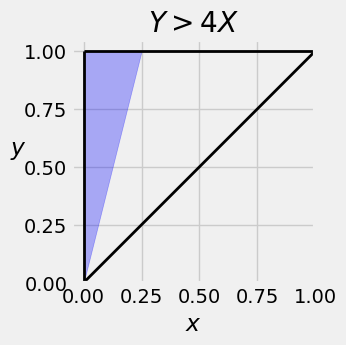

Suppose you want to find

To find the region of integration, notice that for fixed

17.1.5.1. By SymPy#

Integral(f, (x, 0, y/4), (y, 0, 1))

Integral(f, (x, 0, y/4), (y, 0, 1)).doit()

5/32

17.1.6. Example 2#

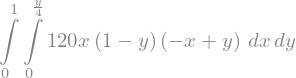

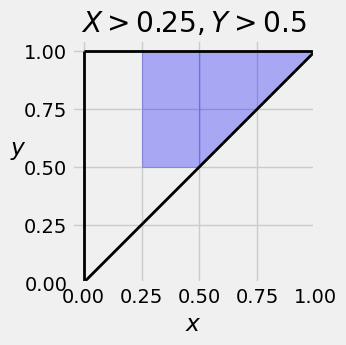

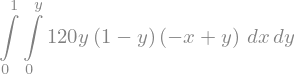

Suppose you want to find

Now

You can crank that out by hand or use SymPy.

Integral(f, (x, 0.25, y), (y, 0.5, 1))

Integral(f, (x, 0.25, y), (y, 0.5, 1)).doit()

See More

17.1.7. Expectation#

Let

provided the integral exists, in which case it can be carried out in either order:

This is an application of the non-linear function rule for expectation, applied to two random variables with a joint density.

As an example, let’s find

Here

17.1.7.1. By SymPy#

Remember that x and y have already been defined as symbolic variables that are positive.

ev_y_over_x = Integral((y/x)*f, (x, 0, y), (y, 0, 1))

ev_y_over_x

ev_y_over_x.doit()