8.5. Method of Indicators#

This is a powerful method for finding expected counts. It is based on the observation that among

If

where for each

Now recall that if

So

It is important to note that the additivity works regardless of whether the trials are dependent or independent.

See More

8.5.1. Expectation of the Binomial#

Let

where for each

Examples of use:

The expected number of heads in 100 tosses of a coin is

The expected number of heads in 25 tosses is 12.5. Remember that the expectation of an integer-valued random variable need not be an integer.

The expected number of times green pockets win in 20 independent spins of a roulette wheel is

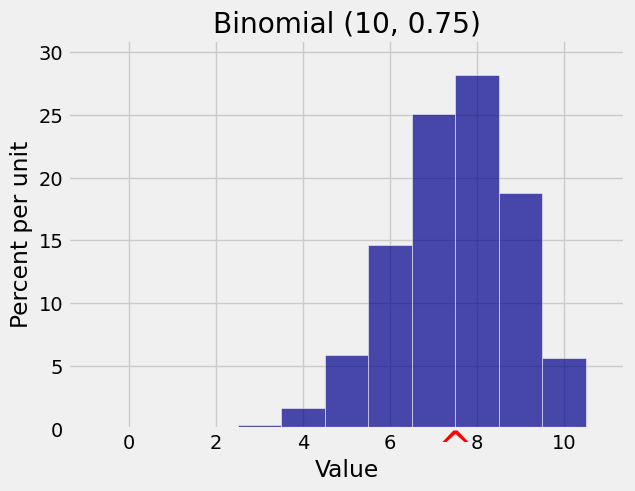

k = np.arange(11)

probs = stats.binom.pmf(k, 10, 0.75)

bin_10_75 = Table().values(k).probabilities(probs)

Plot(bin_10_75, show_ev=True)

plt.title('Binomial (10, 0.75)');

Notice that we didn’t use independence. Additivity of expectation works whether or not the random variables being added are independent. This will be very helpful in the next example.

See More

8.5.2. Expectation of the Hypergeometric#

Let

where for each

This is the same answer as for the binomial, with the population proportion of good elements

Examples of use:

The expected number of red cards in a bridge hand of 13 cards is

The expected number of Independent voters in a simple random sample of 200 people drawn from a population in which 10% of the voters are Independent is

These answers are intuitively clear, and we now have a theoretical justification for them.

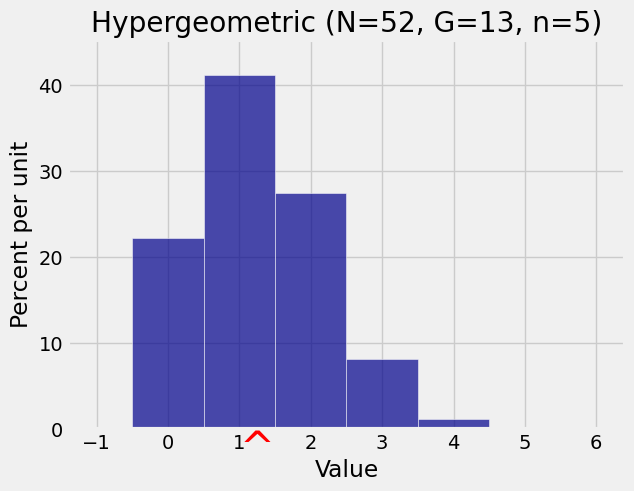

# Number of hearts in a poker hand

N = 52

G = 13

n = 5

k = np.arange(6)

probs = stats.hypergeom.pmf(k, N, G, n)

hyp_dist = Table().values(k).probabilities(probs)

Plot(hyp_dist, show_ev=True)

plt.title('Hypergeometric (N=52, G=13, n=5)');

Quick Check

A deck contains

(a) if the cards are drawn with replacement

(b) if the cards are drawn without replacement

Answer

(a)

(b)

8.5.3. Number of Missing Classes#

A population consists of four classes of individuals, in the proportions 0.4, 0.3, 0.2, and 0.1. A random sample of

If

where for each

For Class

The four indicators aren’t independent but that doesn’t affect the additivity of expectation.

See More

Quick Check

A deck of 52 cards is dealt (at random without replacement) to four players, so that each player gets a hand of 13 cards. To find the expected number of hands that have no aces, which would you use?

(i) Four indicators, one for each ace

(ii) Four indicators, one for each hand

(iii) Thirteen indicators, one for each card in a hand

(iv) Fifty-two indicators, one for each card in the deck

Answer

(ii)