23.3. Multivariate Normal Density#

It is reasonable to expect that if a random vector

For an example of what could go wrong, let

Another example is

For a data scientist, there is no benefit in carrying around variables that are deterministic functions of other variables in a dataset. So we will avoid degenerate cases such as those above. To do this, let’s make an observation about the linear transformations involved.

In both cases, if you write

Thus we are going to restrict the definition of multivariate normal vectors to invertible linear transformations of i.i.d. standard normal vectors and positive definite covariance matrices.

See More

23.3.1. The Density#

From now on, we will usually say “density” even when we mean “joint density”. The dimension of the random vector will tell you how many coordinates the density function has.

Let

We will say that the elements of

You should check that the formula is correct when

You should also check that the formula is correct in the case when the elements of

When

See More

In lab you went through a detailed development of the multivariate normal joint density function, starting with

See More

Definition 1:

Definition 2:

Definition 3: Every linear combination of elements of

At the end of this section there is a note on establishing the equivalences. Parts of it are hard. Just accept that they are true, and let’s examine the properties of the distribution.

The key to understanding the multivariate normal is Definition 1: every multivariate normal vector that has a density is an invertible linear transformation of i.i.d. standard normals. Let’s see what Definition 1 implies for the density.

See More

See More

23.3.2. Quadratic Form#

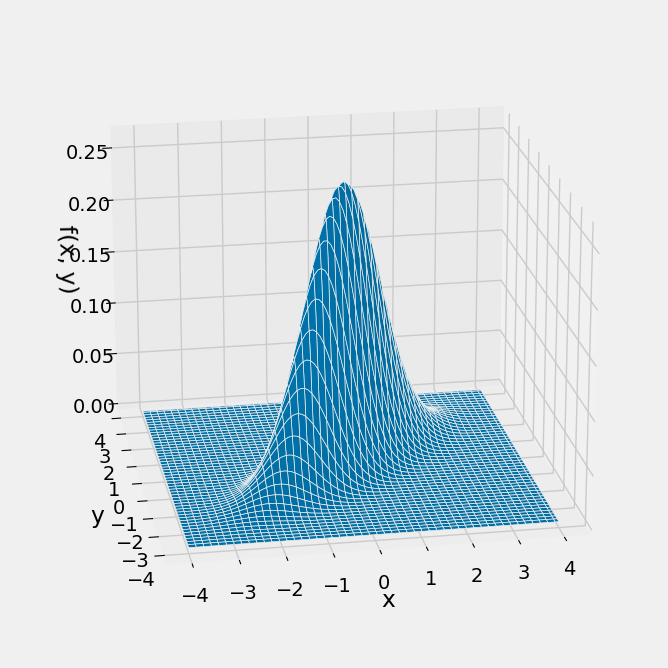

The shape of the density is determined by the quadratic form

Here is the joint density surface of standard normal variables Plot_bivariate_normal(mu, cov) where the mean vector mu is a list and the covariance matrix is a list of lists specifying the rows.

mu = [0, 0]

cov = [[1, 0.8], [0.8, 1]]

Plot_bivariate_normal(mu, cov)

Note the elliptical contours, and that the probability is concentrated around a straight line.

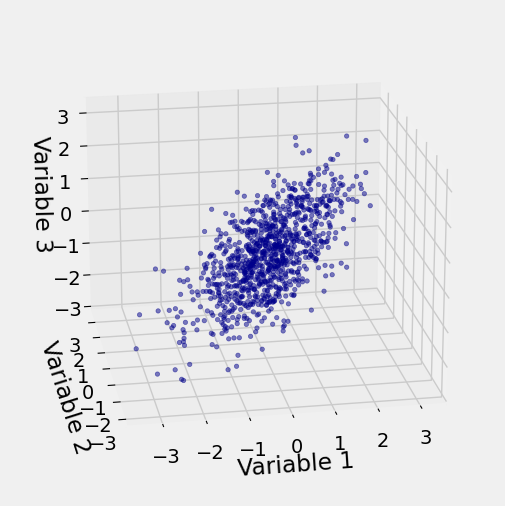

In more than two dimensions we can no longer draw joint density surfaces. But in three dimensions we can make i.i.d. draws from a multivariate normal joint density and plot the resulting points. Here is an example of the empirical distribution of 1000 observations of standard normal variables

The call is Scatter_multivariate_normal(mu, cov, n) where n is the number of points to generate. The function checks whether the specified matrix is positive semidefinite.

mu2 = [0, 0, 0]

cov2 = [[1, 0.6, 0.5], [0.6, 1, 0.2], [0.5, 0.2, 1]]

Scatter_multivariate_normal(mu2, cov2, 1000)

To see how the quadratic form arises, let

By multiplication of the marginals, the joint density of

The preimage of

and so by change of variable the quadratic form in the density of

Let

The covariance matrix of

So the quadratic form in the density of

See More

23.3.3. Constant of Integration#

By linear change of variable, the density of

where

Therefore the constant of integration in the density of

We have shown how the joint density function arises and what its pieces represent. In the process, we have proved the Definition 1 implies Definition 2. Now let’s establish that all three definitions are equivalent.

23.3.4. The Equivalences#

Here are some pointers for how to see the equivalences of the three definitions. One of the pieces is not easy to establish.

Definition 1 is at the core of the properties of the multivariate normal. We will try to see why it is equivalent to the other two definitions.

We have seen that Definition 1 implies Definition 2.

To see that Definition 2 implies Definition 1, it helps to remember that a positive definite matrix

So Definitions 1 and 2 are equivalent.

You already know that linear combinations of independent normal variables are normal. If

Showing that Definition 3 implies Definition 1 requires some math. Multivariate moment generating functions are one way to see why the result is true, if we accept that moment genrating functions determine distributions, but we won’t go into that here.