9.1. Probability by Conditioning#

The theory in this section isn’t new. It’s the old familiar multiplication rule. We are just going to use it in the context of processes indexed by time, in a method that we are going to call conditioning on early moves.

See More

9.1.1. Winning a Game of Dice#

Suppose Jo and Bo play the following game. Jo rolls a die, then Bo rolls it, then Jo rolls again, and so on, until the first time one of them gets the face with six spots. That person is the winner.

Question. What is the chance that Jo wins?

Answer. Before you do any calculations, notice that the game isn’t symmetric in the two players. Jo has the advantage of going first, and could win on the first roll. So the probability that Jo wins should be greater than half.

To see exactly what it is, notice that there’s a natural recursion or “renewal” in the setup. For Jo to win, we can condition on the first two moves as follows:

either Jo wins on Roll 1;

or Jo gets a non-six on Roll 1, then Bo gets a non-six on Roll 2, and then the game starts over and Jo wins.

So at Time 0 (that is, before the dice are rolled), let

This is easy to solve.

which is greater than half as we had guessed.

Quick Check

I have a coin that lands heads with chance

Let

(a) Find an equation for

(b) Solve the equation to find the chance that I am the winner.

Answer

(a)

(b)

9.1.2. Gambler’s Ruin: Fair Coin#

Let

Now suppose the gambler has a stopping rule: he will stop once his net gain is

At each toss we will keep track of the gambler’s net gain. So he will start out at 0 and stop when the he gets to

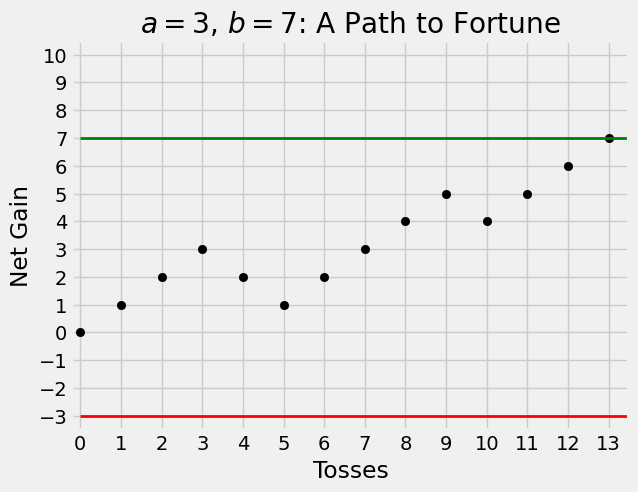

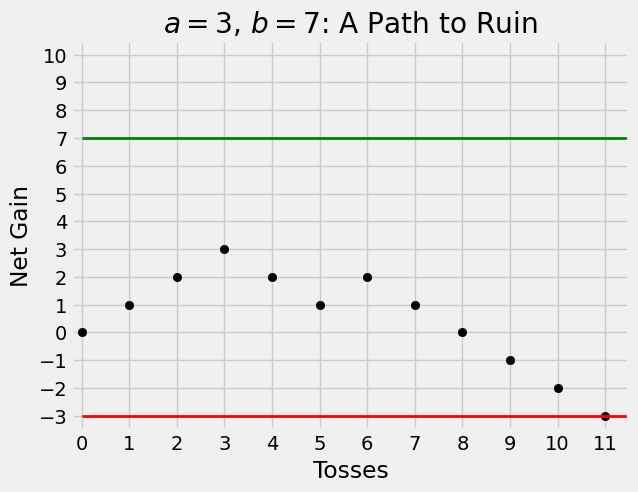

It’s a good idea to start visualizing the random trajectory of the gambler’s net gain as a path. Here are two graphs that assume

Question. What is the probability that the gambler is ruined?

Answer. You can see from the paths above that at the first step the gambler’s net gain will be either -1 or 1, and then we will have to work out the probability of ruin from that point.

For any

The chance that we are looking for is

By conditioning on the first move, we can see that

with the “edge cases” defined as

Write the left hand side of the equation as

The successive differences are equal, which means that

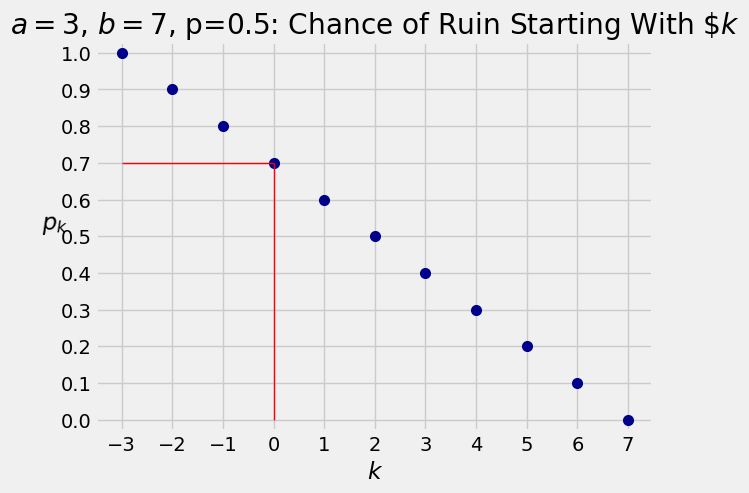

Here is the line assuming

For general

The chance that the gambler ends up gaining

For fixed

9.1.3. Gambler’s Ruin: Unfair Coin#

If the gambler bets on tosses of a coin that lands heads with

where

as before. Now the rearrangement is

which means that the ratio of the successive differences is constant and equal to

and therefore the chance of ruin is

Note that if

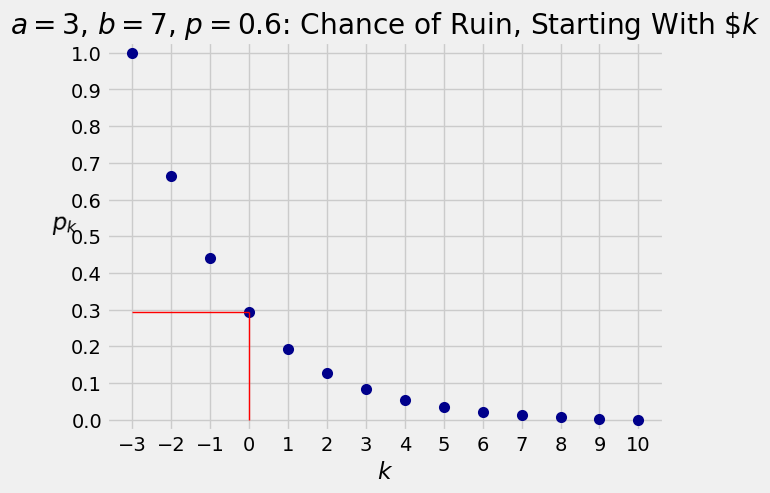

Here is a graph of the ruin probabilities, for